On the Opening of Calder Gardens: The Surprise Element

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej09.22.2025

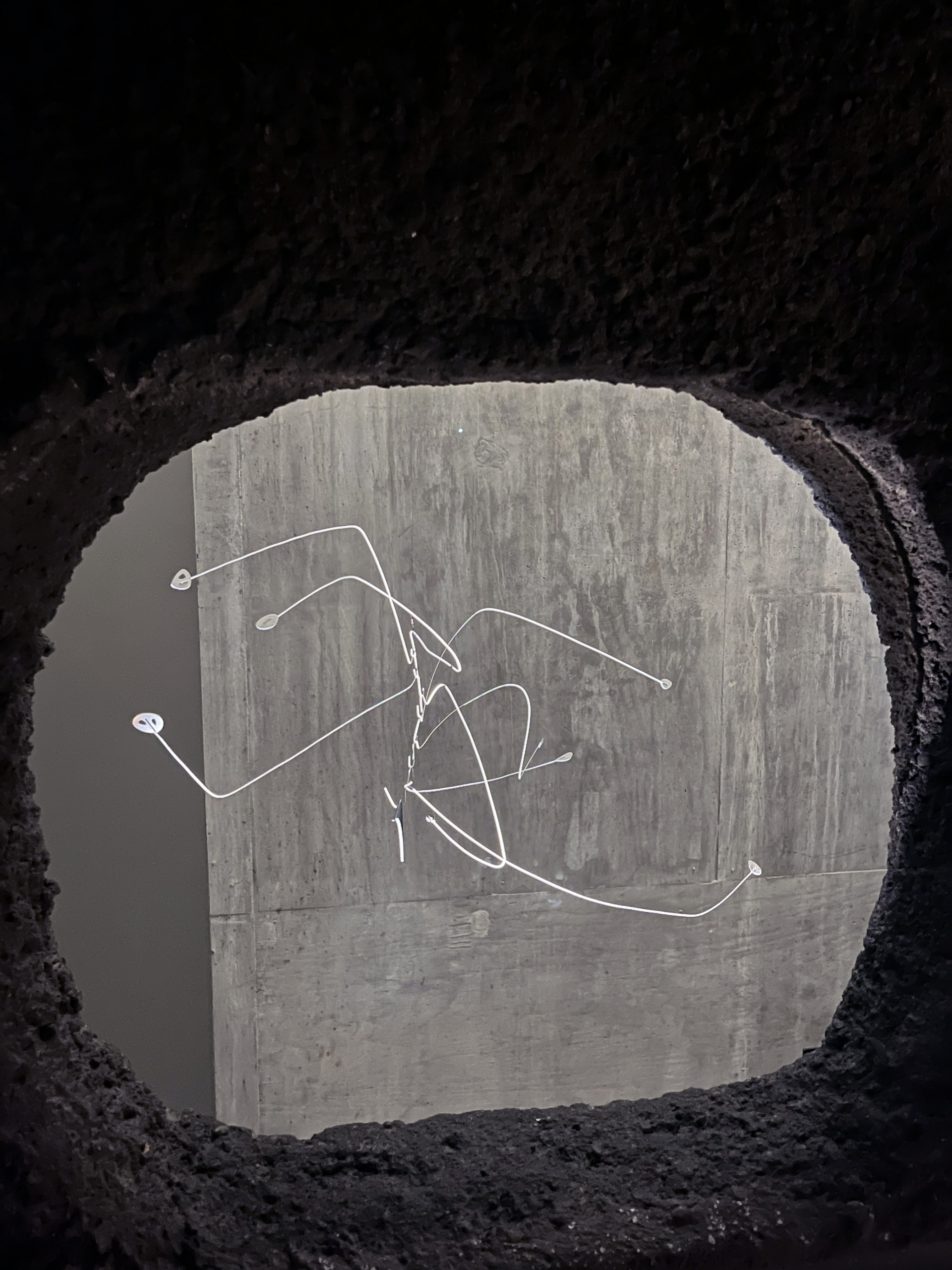

On Saturday at the opening of the Calder Gardens in Philadelphia, descending Herzog & de Meuron's volcanic black stairway, I caught a mobile through what might have been a ship's porthole—suspended there like a daddy long-legs you might find mangled, still twitching.

The Calder Foundation has always taken radical risks for an institution of its stature. At David Kordansky Gallery in 2023 Richard Tuttle created new armatures for Calder sculptures, his "Calder Corrected" series—as if the mobiles needed completing after all these years. At Venus Over Manhattan in 2017 a curator cut a hole clean through the ceiling, as if a rotating blade from one of Calder's stabiles had torn through the plaster, making literal what Sartre saw in 1946: these objects that 'waver and hesitate' contain their own violence.

Herzog & de Meuron's building is disorienting in the best way—a spatial labyrinth where you lose your compass and might miss entire sculptures on first pass. I nearly walked by Eucalyptus (1940), tucked into what seemed an Escher-like impossibility—suspended in a seam in space that shouldn't exist. The architects have created negative sculpture, voids and compressions that make Calder's work appear to have generated the space around it rather than simply occupying it.

Sartre wrote about watching a hammer in Calder's studio perpetually missing its gong, then suddenly, "when you were least expecting it," striking dead center. This new building operates on the same principle—withholding, misdirecting, then revealing. The Foundation seems to understand that reverence kills art faster than neglect. By allowing contemporary artists and architects to actively engage with Calder's legacy, they keep his artwork alive.

Image: Alexander Calder, Tentacles, 1947 installed at the Calder Gardens, Philadelphia