The Collector: Agnes Gund

The Collector09.24.2025

Agnes Gund was a collector and patron who championed contemporary arts, uplifted marginalized artists, and treated philanthropy like a full-time job.

Known as Aggie, she was raised in Ohio, where her father, George Gund II, was president of the Cleveland Trust Company, a major bank at the time. Her mother, Jessica Roesler Gund, oversaw the home and often engaged her daughter in discussion about music and art. “I spent a lot of time in the marvellous Cleveland Museum of Art – in its programmes, its Saturday classes,” she said. [1]

“My interest in collecting art began very early,” Gund said in 2019. “As a girl, I loved the art at home, much of it scenes of the American West and paintings by the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla, which my father collected.” [Ibid.]

In the ’50s, after her mother’s death, she was sent to Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut. There, she had “a wonderful art history teacher who was really engaging and formative in shaping my love of art,” Gund told Sotheby’s. “She seemed to recognize that I had an eye for looking at things, that my whole nature was tuned to being visual.” [Ibid.]

From there, she studied history at Connecticut College for Women (now Connecticut College) and married her first husband, Albrecht Saalfield, a teacher and publishing heir. Gund’s father died in 1966 and she started using her trust to buy art. A 1964 Henry Moore sculpture of a horse (“Three-Way Piece No. 2”) was her first major acquisition. “But the children were playing on it so I gave it to the Cleveland Museum,” she said. [2] She initially wanted to collect Old Master drawings but “could not live in the lowlight conditions they require.” [1]

“My earliest interest was in prints, drawings, even sketches and notebooks,” Gund said. “For me, drawings capture the very personalities of their makers, in immediate and intimate ways – sometimes more so than more formalized work.” [Ibid.]

She soon purchased work by Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Claes Oldenburg, and Mark Rothko. All became close friends with Gund except the deceased Rothko. Her collection featured many female artists, including Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis, Kara Walker, and Lorna Simpson.

“My friendships with artists, as well as a sensitivity to the challenges facing women artists and artists of color, have been formative in shaping my collection which is deeply personal and deeply autobiographical.” [1]

In 1967, Gund joined the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art. Her tenure as president from 1991 to 2002 is often considered the museum’s “golden era.” She expanded the museum’s educational programs and pushed the institution to acquire works by women and artists of color. An avid supporter of contemporary arts, she helped launch MoMA PS1 and she oversaw MoMA’s $858 million expansion, which doubled the museum's exhibition space and was completed in 2004. She became president emerita of MoMA in 2005, a title she held until her death. [3]

Nearly all her collection was promised to museums, and during her lifetime she donated hundreds of works to the Cleveland Museum of Art, the MoMA, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “It could be because I feel guilty about having so much more than most people,” she told Crain’s New York Business in 2006. “If I can have it, others should be able to enjoy it.” [4]

In 1977, she started Studio in a School, a highly successful nonprofit that brought arts education to public schools all over New York City. “I just couldn’t believe that they wouldn’t still have an arts and music program at least available,” Gund once said of the city’s budget cuts. “Our whole idea was to have artists who were the teachers.” Said teachers included Mark di Suvero, Jeff Koons, Julie Mehretu, and Fred Wilson. [5]

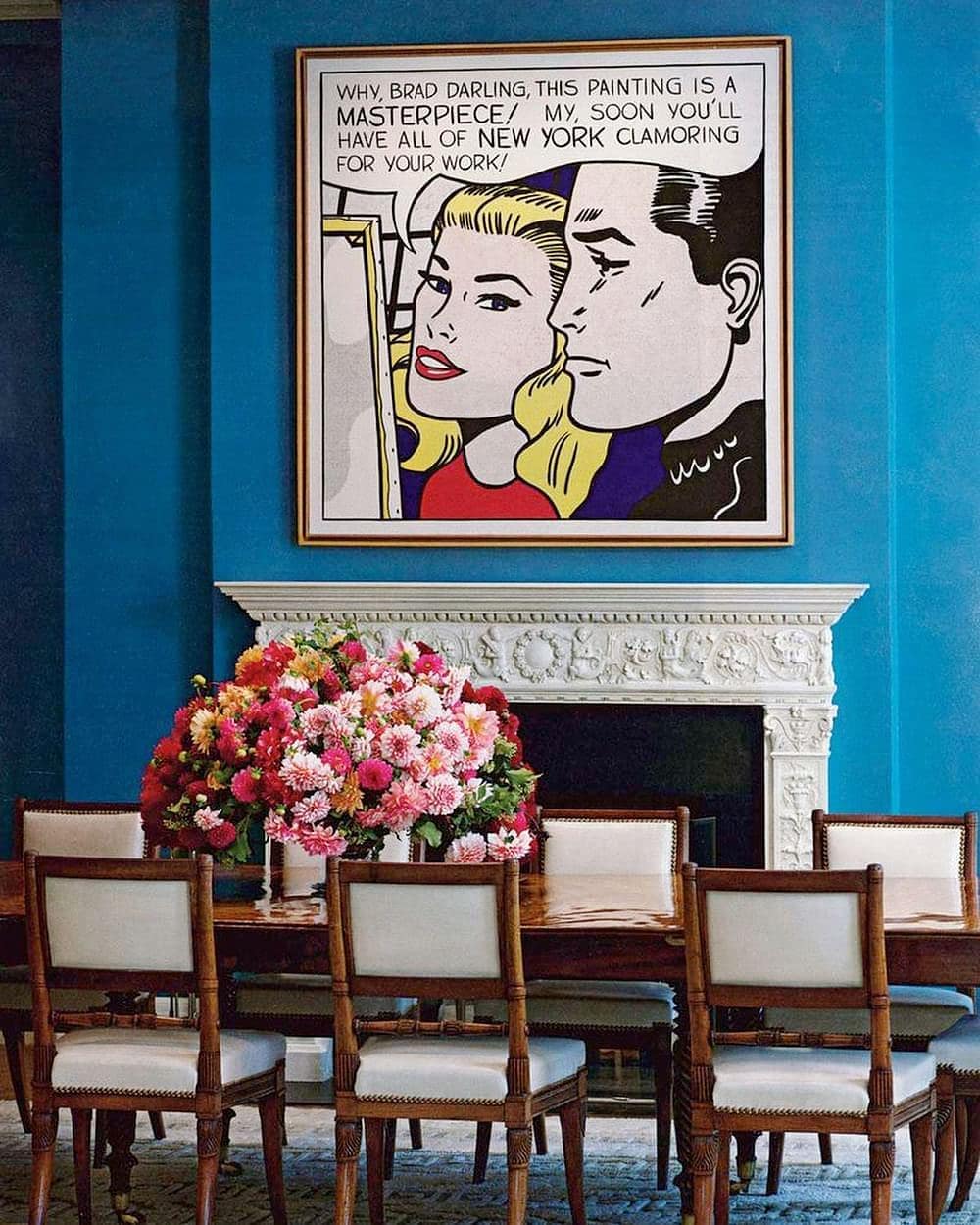

In 2017, Gund sold her treasured Roy Lichtenstein “Masterpiece” (1962) for $150 million ($165 million with fees) to collector and hedge fund investor Steven A. Cohen. She used $100 million from the sale to establish the Art for Justice Fund, a five-year initiative managed by Ford Foundation that provided grants to promote criminal justice reform. [6]

In 2023, Ms. Gund sold another Lichtenstein painting, “Mirror #5” (1970), in response to the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade. She donated the $3.1 million to two organizations that advocate for reproductive rights. As Gund told Christie’s of the decision, “I felt compelled to part with this beloved work by an artist who means so much to me because I believe in the power of art as a tool for advocacy and inspiration.” [4]

SOURCES

[1] “Agnes Gund: Collector, Philanthropist and Women's Advocate.” Sotheby’s, Feb 27, 2019 https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/agnes-gund-collector-philanthropist-and-womens-advocate

[2] Bernstein, Jacob. “Is Agnes Gund the Last Good Rich Person?” The New York Times, November 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/03/style/agnes-gund-philanthropy.html

[3] Pogrebin, Robin. “A Patron Gives, of Herself and Her Art.” The New York Times, November 6, 2014.

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/07/giving/a-patron-gives-of-herself-and-her-art.html

[4] Grimes, William. “Agnes Gund, Who Oversaw a Major Expansion of MoMA, Dies at 87.” The New York Times, September 19, 2025.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/19/arts/agnes-gund-dead.html

[5] Cascone, Sarah. “Why Was 1977 Such a Boom Year for Upstart New York Art Institutions?” Artnet, December 17, 2017

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/oral-history-why-were-so-many-new-york-art-organizations-founded-40-years-ago-1073045

[6] Pogrebin, Robin. “Agnes Gund Sells a Lichtenstein to Start Criminal Justice Fund.” The New York Times, June 11, 2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/11/arts/design/agnes-gund-sells-a-lichtenstein-to-start-criminal-justice-fund.html

Image: Roy Lichtenstein, "Masterpiece" (1962)