The Collector: Ben Heller

The Collector08.06.2025

Mark Rothko once dubbed Ben Heller’s apartment “the Frick of the West Side.” The textile executive and New York native filled his home with works by Pollock, Kline, Newman, Giacometti, Johns, Gorky, and Still, alongside pre-Columbian, African, and ancient sculpture. [1]

Born in 1925, Heller discovered modern art while honeymooning in 1949, after seeing exhibitions of Georges Braque and Paul Gauguin. He returned to New York and bought a Braque still life and an African fetish figure. Though he started with European modernism, he soon turned to contemporary art.

Around 1953, during a studio visit with his soon-to-be-friend Jackson Pollock, Heller bought “One, Number 31, 1950” for $8,000, to be paid in installments. [2] Pollock included “No. 6, 1952” in the deal and Heller also added “Echo” for $3,500. “It was the first of our truly large paintings and from it we learned how penetrating, changing, enlarging and vital an experience living with such a painting is,” Heller wrote of “One.” “From its acquisition we came to a new understanding of the import of an act, of risk.” [3]

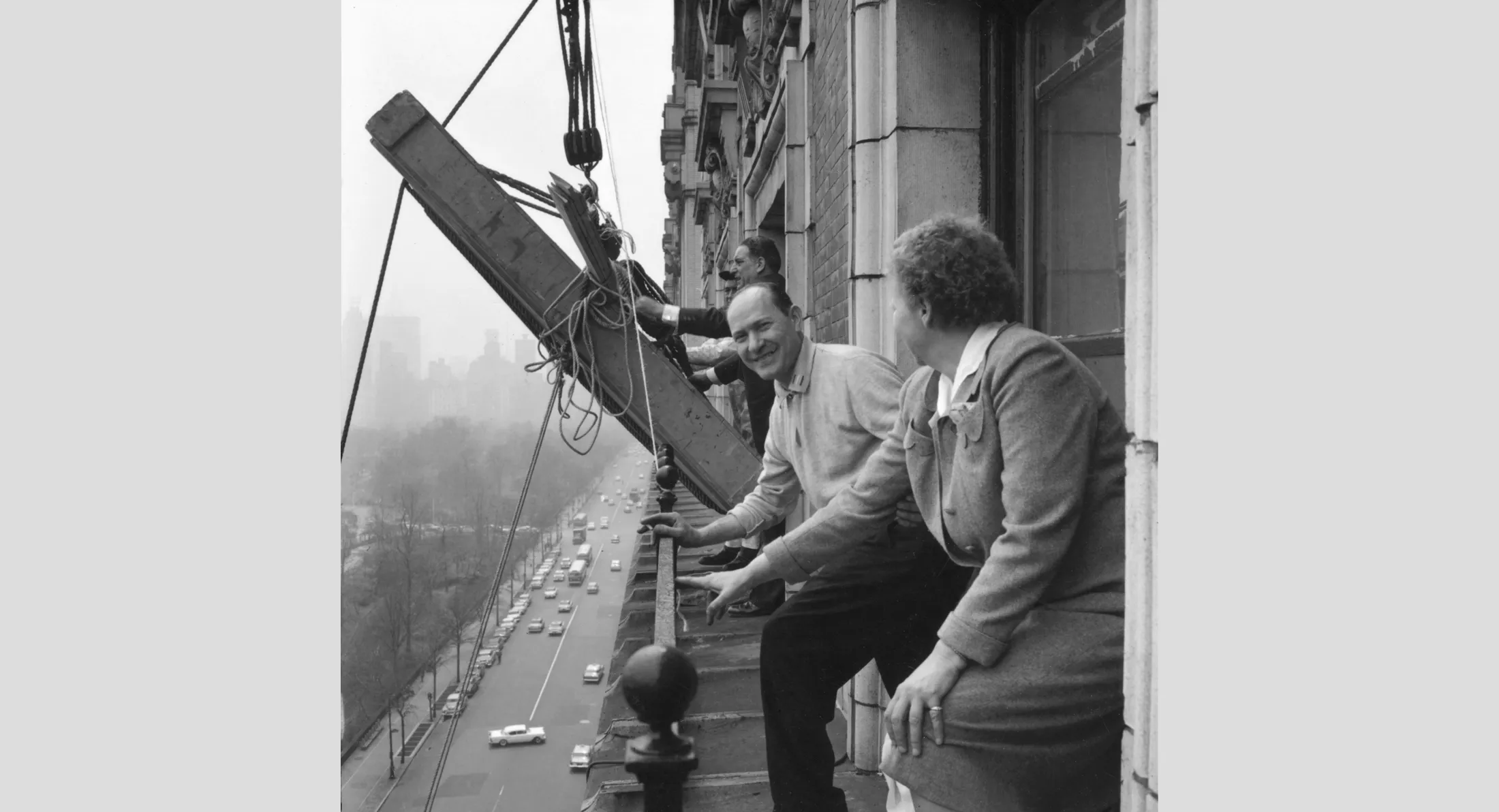

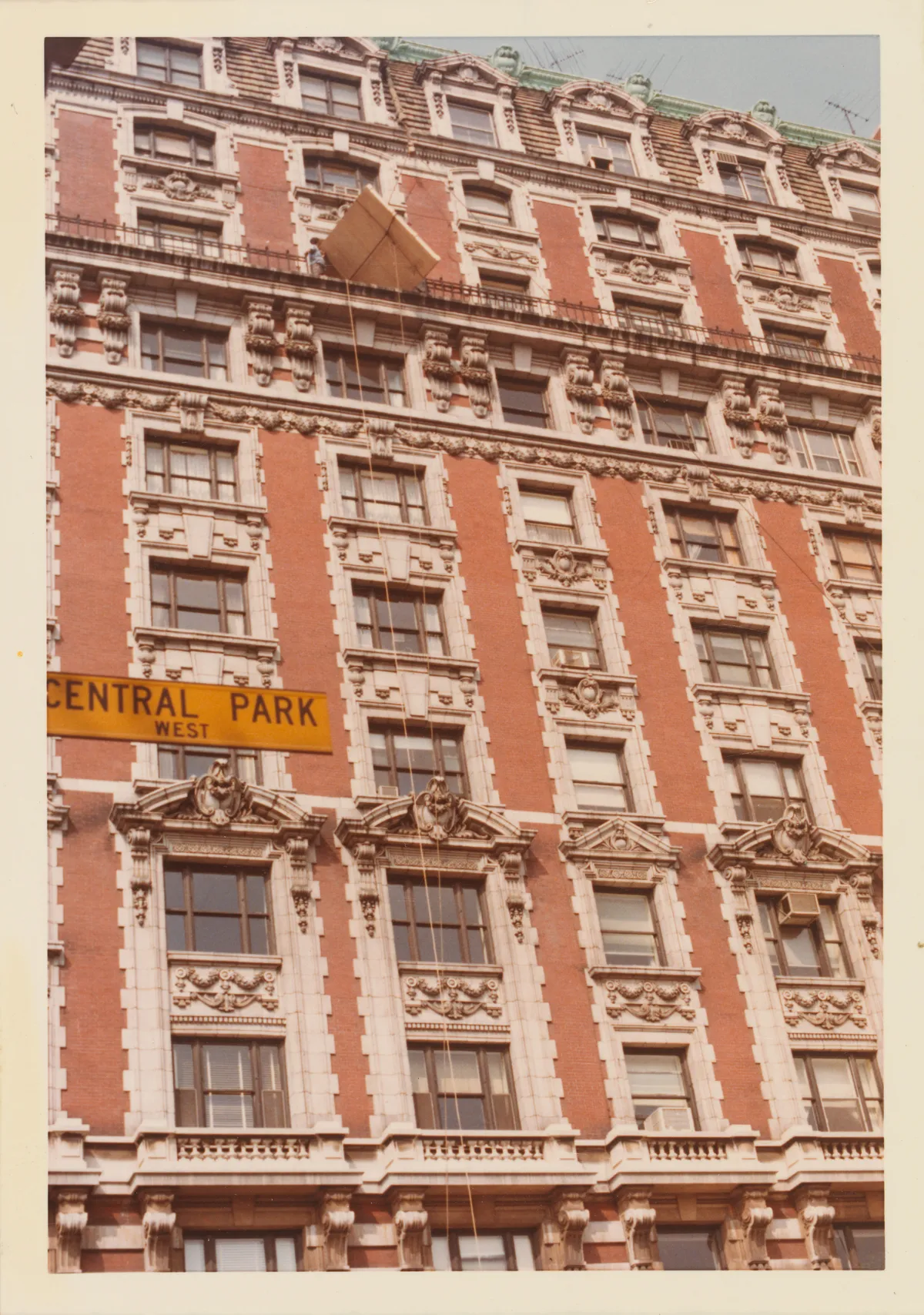

Heller took substantial risks on emerging artists before Abstract Expression was canonized as a historic visual turning point. MoMA largely ignored the style—Robert Motherwell once quipped that one would have to go to Heller’s apartment to see modern art—until the late ’60s, when curator William S. Rubin actively expanded the museum’s holdings. [4] Heller assisted by gifting and selling works including “One,” which MoMA bought in 1968 for $350,000. He often loaned pieces from his collection—sometimes requiring a crane to move them from his tenth-floor apartment.

In 1957, he bought Pollock’s “Blue Poles” (1952) from Fred and Florence Olsen. Working with dealer Max Hutchinson, in 1973 Heller sold the drip painting for $2 million (around $14 million today) to the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. [5] Derided for its high price tag and relocation outside of the U.S.—it also caused a political scandal down under—the sale anticipated the art market’s financialization that came later that year with Sotheby’s Ethel and Robert Scull auction. “Art was becoming big, and collectors were becoming big, and all that stuff was becoming bigger than the work of art,” Heller, who had advised the Sculls, recalled. “It was my sale that woke everyone up to what these paintings were worth on the market.” [6]

Photos courtesy of Ben Heller and the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

SOURCES

[1] Shapiro, Laurie Gwen. “An Eye-Popping Mid-Century Apartment Filled With Pollocks, Klines, and de Koonings.” New York Magazine, October 9, 2020. https://www.curbed.com/2020/10/ben-hellers-mid-century-nyc-apartment.html

[2] Smith, Roberta. “Ben Heller, Powerhouse Collector of Abstract Art, Dies at 93.” The New York Times, May 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/04/obituaries/ben-heller-dead.html

[3] “The Collection of Mr. And Mrs. Ben Heller.” The Museum of Modern Art, Distributed by Doubleday & Company, Inc. Garden City, New York 1961.

[4] Durón, Maximilíano. “Ben Heller, Pioneering Collector of Abstract Expressionism: ‘There’s Nobody Else in That League.’” ArtNews, March 3, 2021.

https://www.artnews.com/feature/who-is-ben-heller-collector-1234584691/

[5] The National Gallery of Australia. “Growing Up With ‘Blue Poles.” Artonview, No 84, Summer 2015. https://bluepoles.nga.gov.au/history/growing-up-with-blue-poles/

[6] Heller, Ben. “The Museum Of Modern Art Oral History Program Interview With: Ben Heller ” Interview by Avis Berman. April 18, 2001. https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/archives/transcript_heller.pdf.

Image: Jackson Pollock, “Blue Poles” (1952) alongside Clyfford Still, “Painting Number 2” (1949) and works by Mark Rothko