The Collector: David M. Solinger

The Collector02.04.2026

In 1945, David M. Solinger (1906-1996) returned to New York from the war in Europe and resumed his legal career. A friend mentioned he was taking painting classes at the Y. The idea stuck. Solinger enrolled in a Monday night class, then studied at the Art Students League. ‘Painting wakes you up,’ he later said. ‘Lawyers need this relaxation. Law is precise; it doesn’t give the imagination much sway. That’s where painting comes in.” [1]

Solinger grew up in New York, the son of second-generation German immigrants who worked in the meat business. Solinger instead pursued higher education, studying at Cornell University and then Columbia Law School. He served in the U.S. Army during the Second World War, enlisting in the public relations arm of his division. [2]

After the war, Solinger resumed his legal career at Solinger and Gordon, the Manhattan law firm he co-founded. He distinguished himself as one of the first lawyers to specialize in the emerging fields of radio and television, advertising, and art law.

Solinger said that the experience of painting courses “opened the door to every facet of visual experience, because it resulted in my becoming interested in and involved with artistic institutions.” His first acquisition came in the late 1940s, when he bought a painting by Hawaiian-born Reuben Tam from Edith Halpert’s legendary Downtown Gallery. “That was an act of great courage, because to spend a few hundred dollars on a painting was the equivalent of spending what was, in the economy and society of that day, more than a month's rent,” Solinger said. “One had to think of it in those terms.” [3]

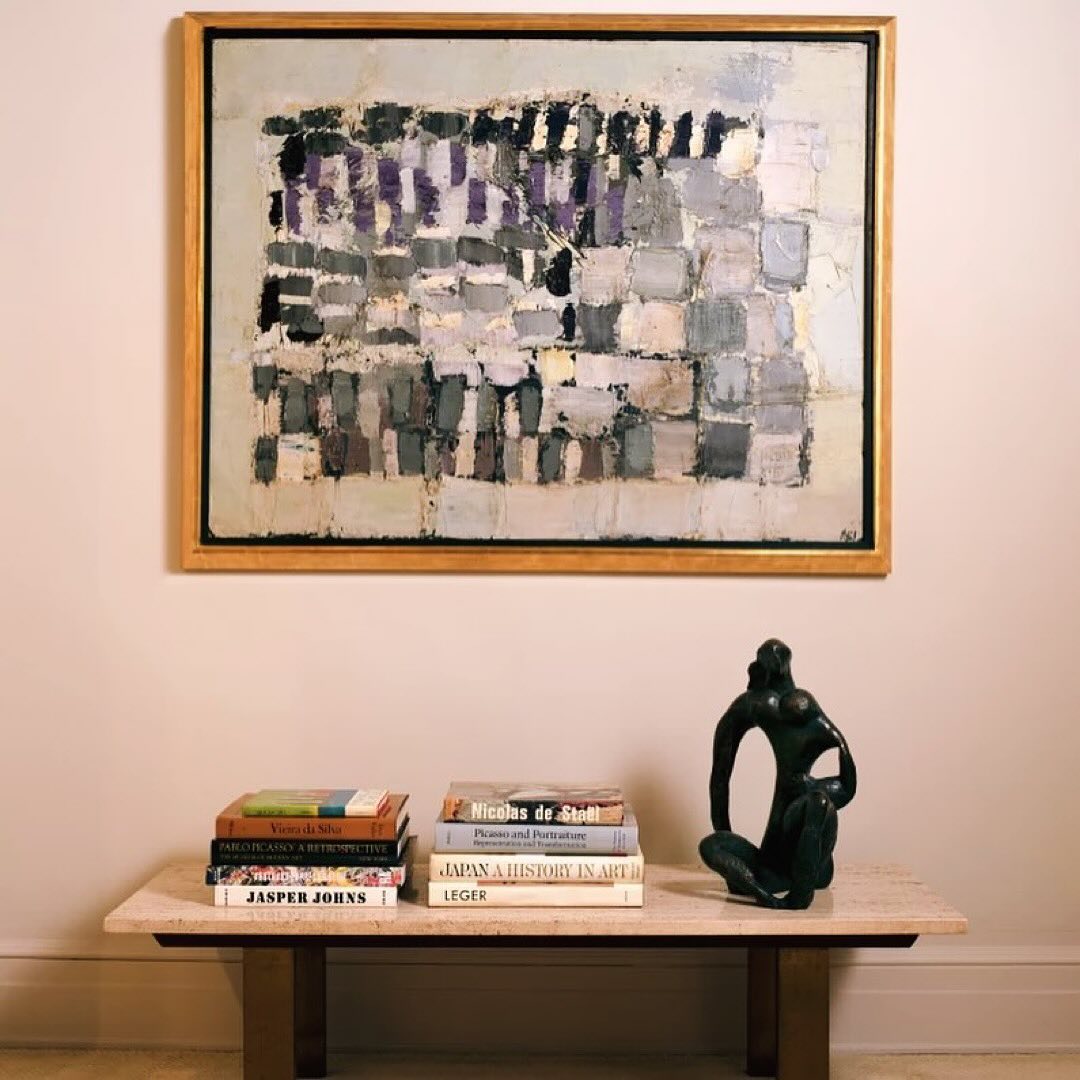

From that point forward, Solinger spent most of his leisure time browsing galleries and museums. “I collected solely because I loved the things I bought, and once I broke the ice, I was relatively unrestrained. I was also very lucky, because paintings, like strawberries, should be bought when they're plentiful and cheap.” [Ibid.] He grew increasingly confident in his aesthetic judgement and perception, which allowed him to single out major talents. From the 1950s to the early 1970s, Solinger built a carefully curated collection of postwar works by names like Paul Klee, Jean Dubuffet, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Willem de Kooning, and Wassily Kandinsky.

“I would say that the thing that prevented me from being a great collector, rather than a very modest collector with a modest collection, is two things,” he said. “I wasn’t bold enough financially. I was bold enough to find, I think, the right artists and the right pictures of those artists, but it was always hard for me to buy with a kind of abandon that some great collectors have.” [Ibid.]

Solinger befriended many of the most influential dealers and gallerists in New York, including Pierre Matisse, Samuel Kootz, Sidney Janis, and Charles Egan. He was friendly with Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, and helped acquire Franz Kline’s “Chief” (1950), a highlight from the artist’s inaugural solo exhibition, for the museum. (Kline later made an oil sketch of the painting on the page of a phone book for Solinger.) He was also close with the artists. He socialized with de Kooning and Dubuffet, studied painting with Hans Hofmann, and acted as legal representative for many others, among them John Marin, Robert Motherwell, and Louise Nevelson. [4]

While visiting Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio in 1951, Solinger saw “Trois hommes qui marchent (Grand plateau)”. He subsequently purchased it through Galerie Maeght, but the work was damaged in transport and sent back to the artist for repairs. Giacometti then recast and re-painted the sculpture to Solinger’s specifications. In 1962, Solinger gave Giacometti’s “Monumental Head” (1960) to MoMA.

In 1956, art historian Lloyd Goodrich invited Solinger to attend a meeting with a small group of people interested in financially supporting the Whitney Museum of American Art, which was then a struggling private institution. A formal non-profit organization called the Friends of the Whitney Museum was born with Solinger at the helm. In 1961, he was among the museum’s first outside trustees, and in 1966, he became President, the first non-family member to hold the position. Under his leadership (which lasted until 1974), the Whitney evolved into an acclaimed public museum. In 1963, he led the effort to construct the Marcel Breuer building at Madison Avenue and 75th Street that would be the museum’s home for nearly 50 years. He was also instrumental in the 1973 opening of the Whitney’s first branch museum at 55 Water Street in lower Manhattan.

He rarely, if ever, sold or traded works. “I have given a number of pictures away, motivated by a desire to enrich the collection of the particular institution, and also to keep my apartment from being unlivable in,” he said. [3] Significant artworks from the Solinger collection fill the walls of the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. He was a founding member and chair of the Johnson Museum Advisory Council at Cornell University, and a long-serving board member of the American Federation of Arts.

SOURCES

[1] Vogel, Carol. “David Solinger, 90, Art Collector And Whitney Museum President.” The New York Times. October 30, 1996

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/10/30/arts/david-solinger-90-art-collector-and-whitney-museum-president.html

[2] “David M. Solinger: A Vision for a New Generation.” Sotheby’s. Oct 25, 2022

https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/david-m-solinger-a-vision-for-a-new-generation

[3] Oral history interview with David M. Solinger, 1977 May 6. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-david-m-solinger-13131

[4] Kazakina, Katya. “The Rarely Seen Art Collection of a Former TV Lawyer Could Sell for $100 Million at Sotheby’s. Artnet. September 29, 2022

https://news.artnet.com/market/david-solinger-sothebys-100m-2183478

Photos: Visko Hatfield courtesy of Sotheby’s

Image: Pablo Picasso, “Femme dans un fauteuil” (1927). In the background: Willem de Kooning, “Collage” (1950); Fernand Léger, “Une femme brune et une plante jaune” (1950)