The Collector: Jacques Doucet

The Collector02.18.2026

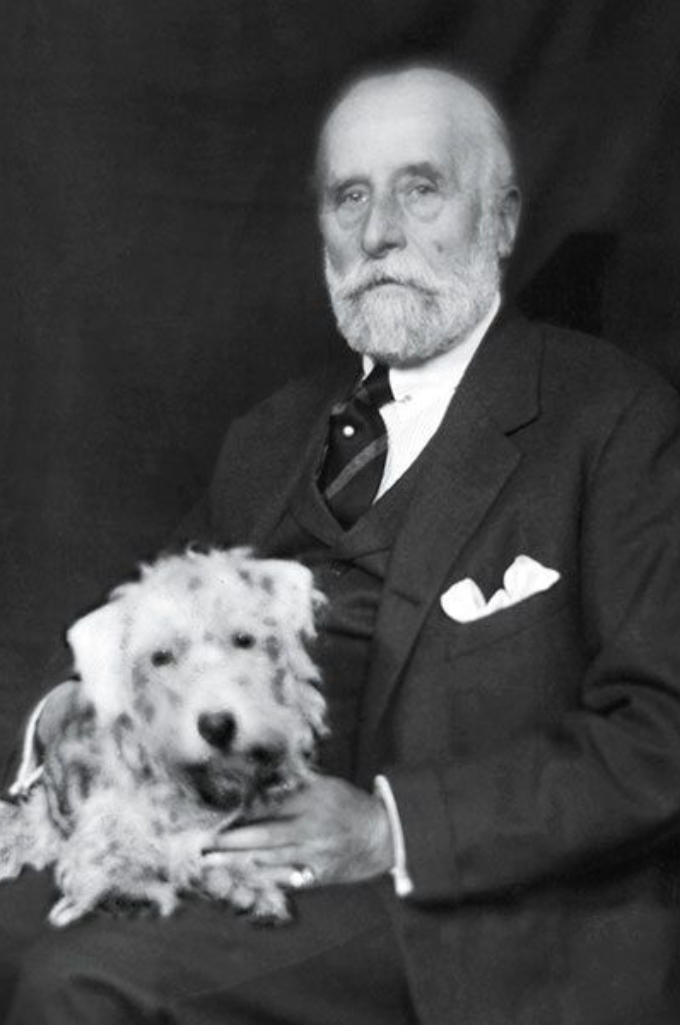

Jacques Doucet, a French fashion designer and arts patron, was one of the most significant collectors of the late 19th and early 20th century. Over the course of five decades, the couturier’s tastes ranged from eighteenth-century douceur de vivre to avant-garde modernism. Toward the end of his life, Doucet reflected on the evolution of his taste, saying, “I was successively my grandfather, my father, my son, and my grandson.” [1]

Doucet was born in Paris in 1853 to a family of clothing makers. Originally purveyors of fine fabrics and lace, the Doucet family soon expanded their offerings to bespoke outfits for royals and heads of state, including French Emperor Napoléon III. In 1875, Doucet joined the family business, Maison Doucet, and under his leadership, it became one of the most important fashion houses of its time, specializing in evening and ball gowns.

Around the turn of the century, Doucet inherited the family business. He would then commission society architect Louis Parent to build an 18th-century-style mansion on rue Spontini in the 16th arrondissement. The building was specifically intended to showcase his 18th-century works of art, and Doucet worked with decorators Adrien Karbowsky and Georges Hoentschel to design the interiors. Completed in 1907, the hôtel particulier housed works by Watteau, de la Tour, Fragonard, and more, in addition to furniture and rare books. [2]

Five years after he moved to Rue Spontini, Doucet sold it all at what would be known as “the sale of the century.” Hosted at Galerie Georges Petit in June 1912, the four-day sale broke records and drew international attention. [3] The final tally was just under $3.1 million—the equivalent of $75 million today. Rumor has it that Doucet parted with his renowned collection due to the death of his mistress. Doucet never elaborated on the cause. In 1921, he explained his change of course as a collector to Félix Fénéon: “Old things, dead things, and I prefer life to dust.” [2]

Doucet used money from the sale to fund a new, modern collection. He relocated to an apartment at Avenue du Bois de Boulogne (now Avenue Foch) in which “works by Sisley, Manet, Soutine, Cézanne, and Van Gogh cohabitate with works by Picasso, Braque, Derain, and Modigliani.” [Ibid.]

Concurrent to Doucet’s art collecting, he was a ravenous collector of books. His Library of Art and Archeology (Bibliothèque d’art et d’archéologie) specialized in materials related to the titular fields, as well as drawings and prints, including examples by Georges Braque, Albert Gleizes, and Picasso. He donated the collection to the University of Paris in 1917, and it has been held at the Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art since 2003. [4]

Between 1913 and 1926, Doucet established a collection of special editions, corrected proofs, letters, and manuscripts related to the modern literary movement. The idea for the Library of Literature (Bibliothèque littéraire) was inspired by André Suarès, who, in 1914, suggested that the designer start a “Montaigne-style library.” Doucet began pursuing the idea two years later and asked Suarès for names to enrich his library “outside of the quartet of which it is made up.” [2] Upon his death, his literary library was bequeathed to the University of Paris, which established the Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques-Doucet.

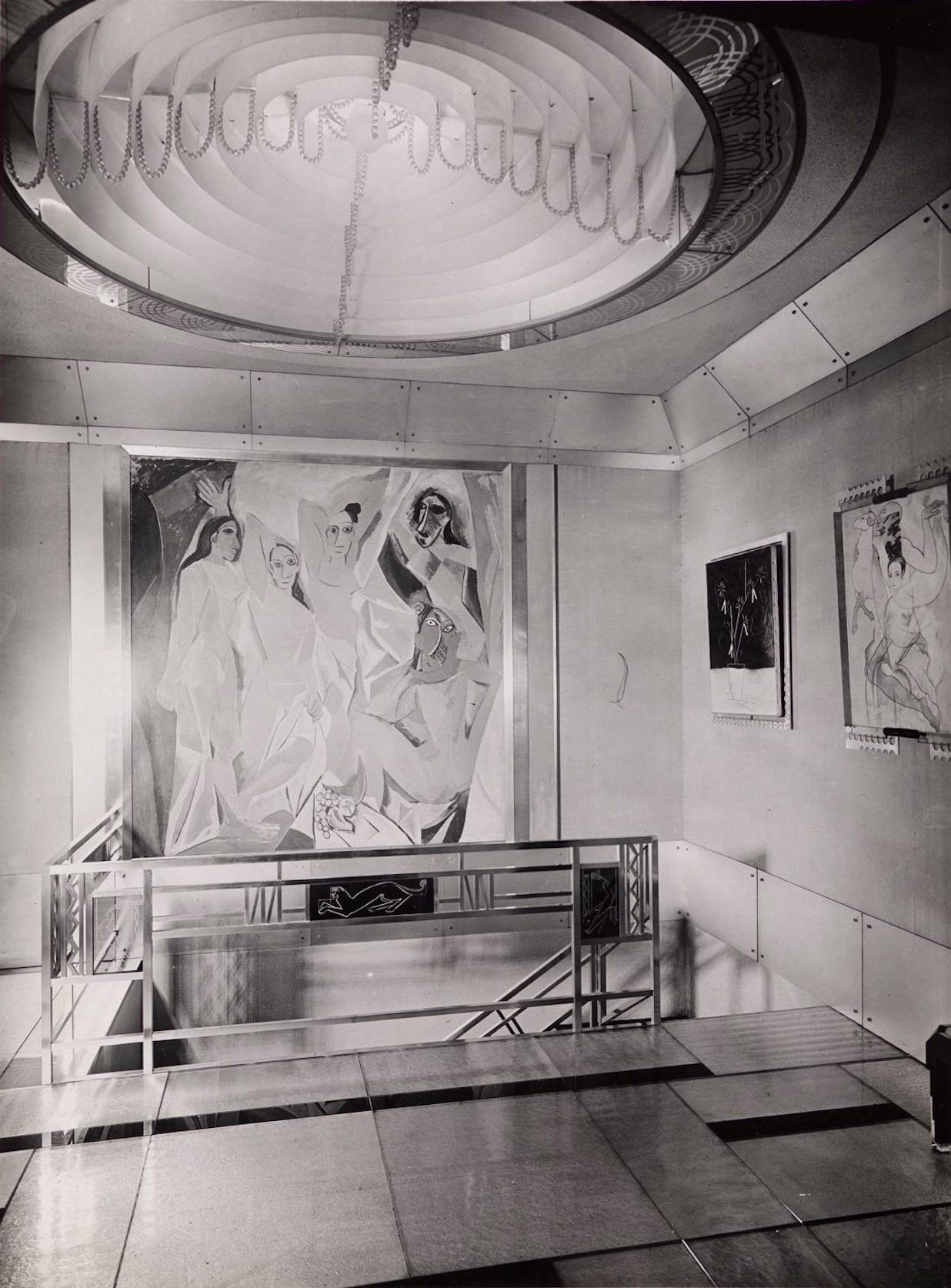

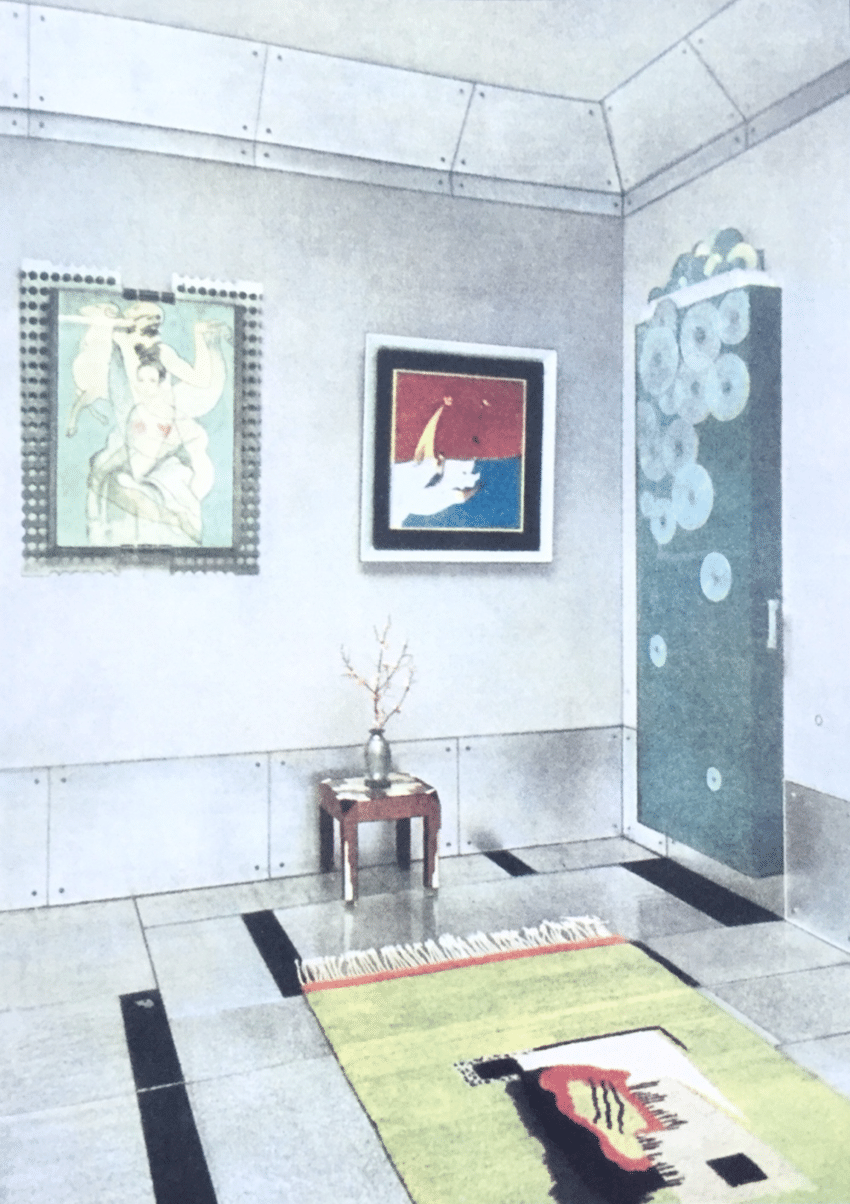

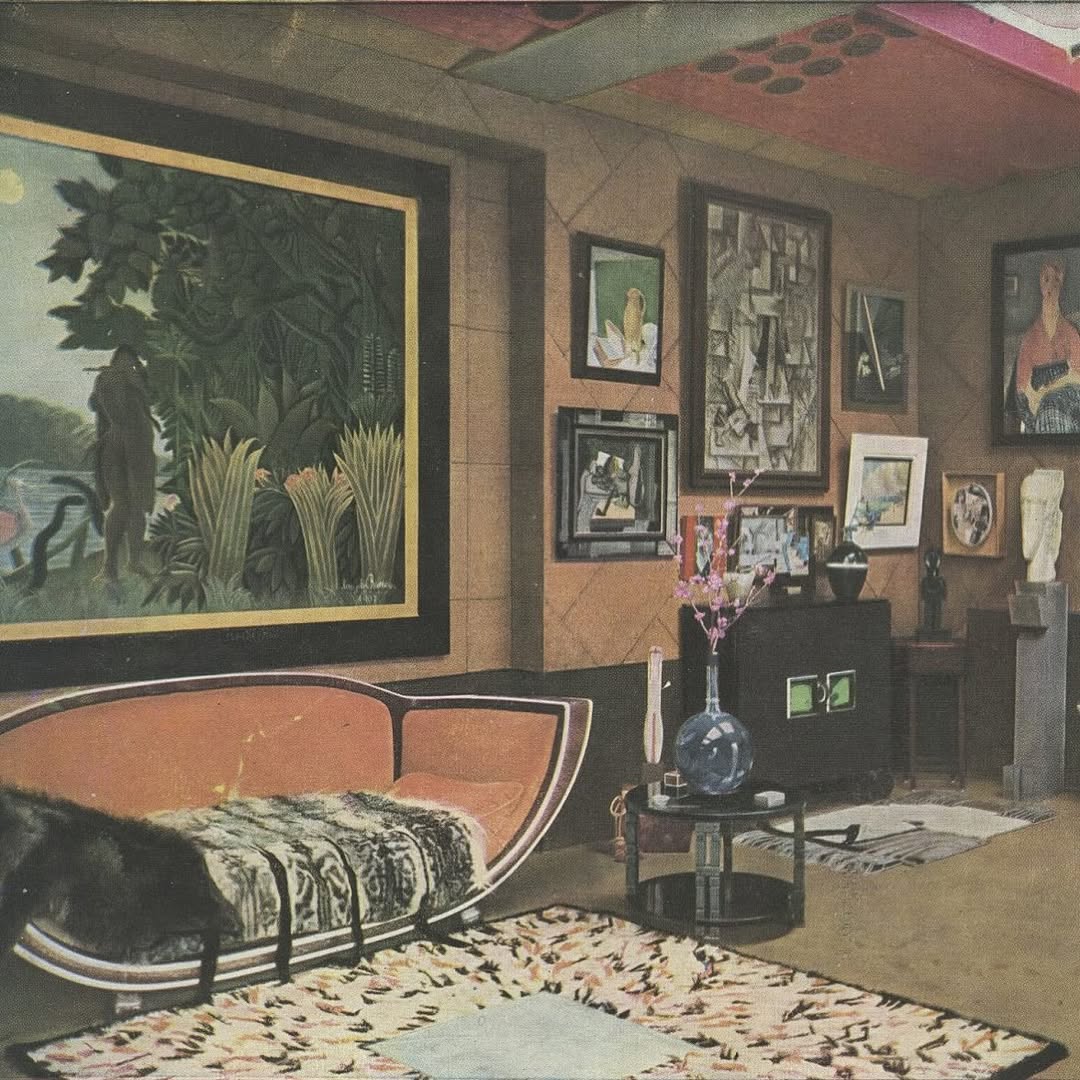

In 1921, Doucet hired the writer and soon-to-be-Surrealist André Breton to be his librarian. Over the years, he would enlist the services of Pierre Reverdy, Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, Raymond Radiguet, Louis Aragon, Robert Desnos and many others. Breton was especially instrumental in Doucet’s art collecting, advising him to buy Henri Rousseau’s “The Snake Charmer” (1907), which was obtained from Robert Delaunay in 1922 under the condition of a bequest to the Louvre upon his death. Breton also encouraged the purchase of Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), acquired from the artist in 1924. Doucet initially rejected paintings by the up-and-coming Joan Miró, calling the Catalan artist “mad, stark mad.” But weeks later, he hung two of the artist’s works at the foot of his bed, saying, “When I wake up in the morning, I see them, and I am happy for the rest of the day.” [1]

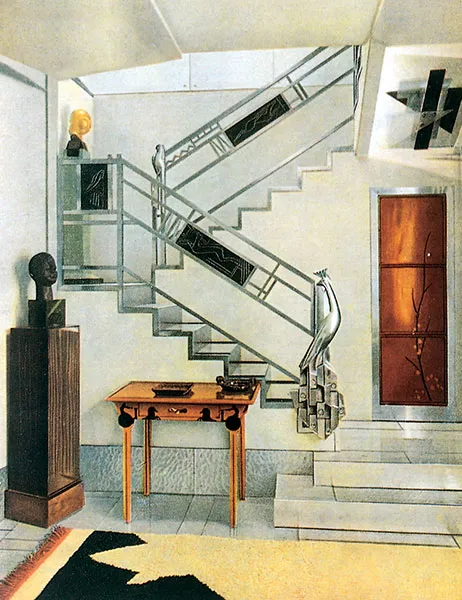

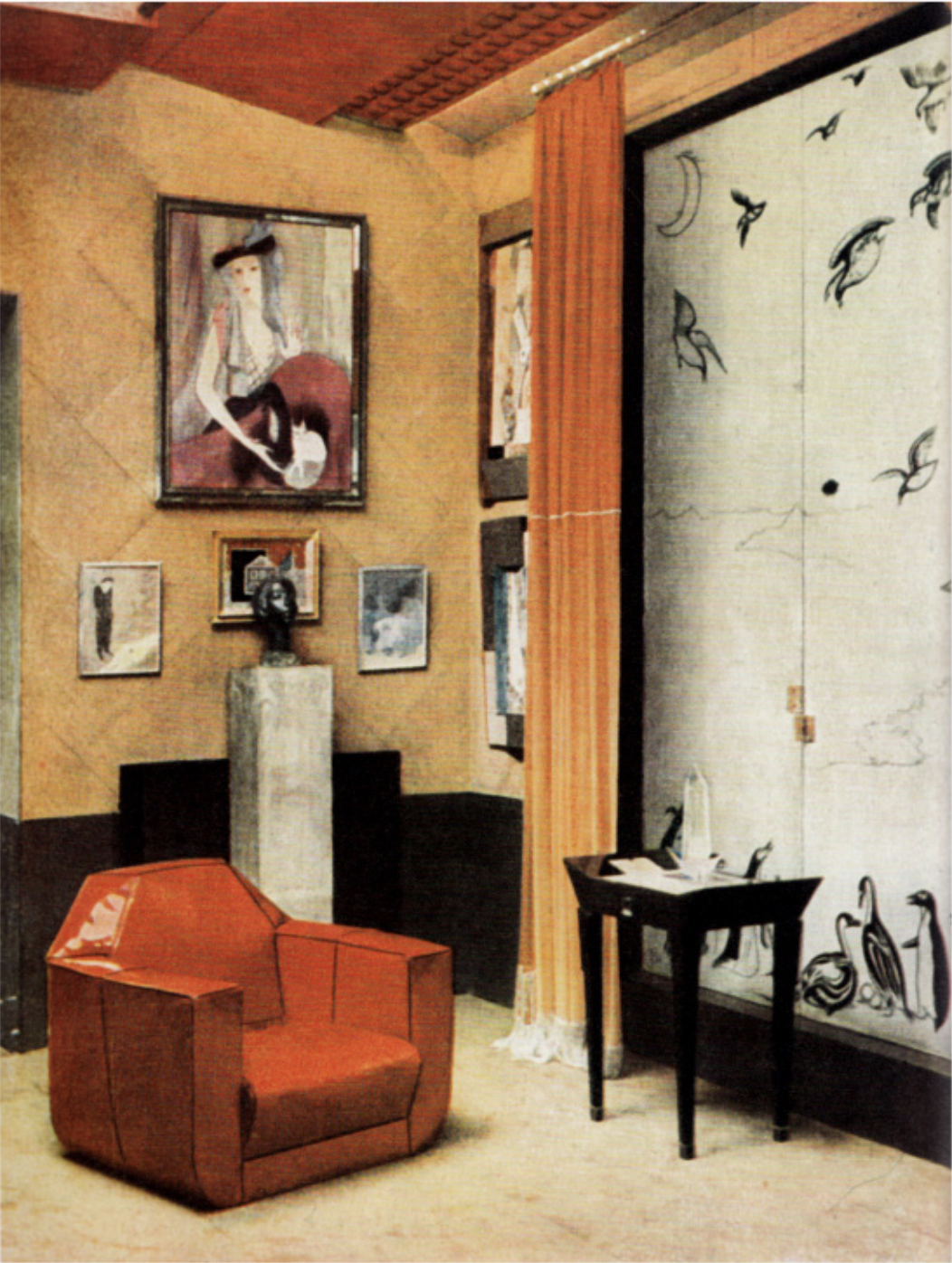

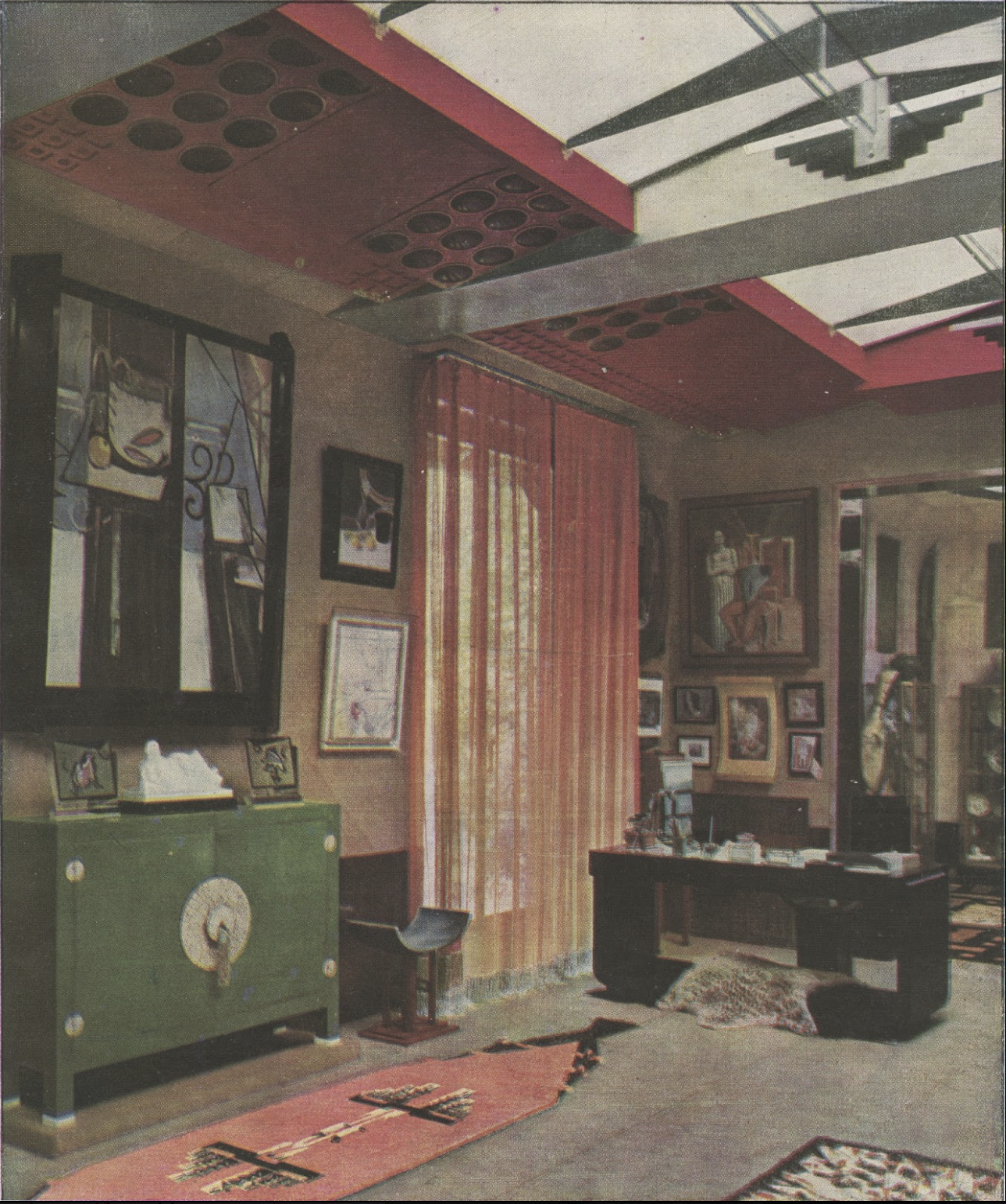

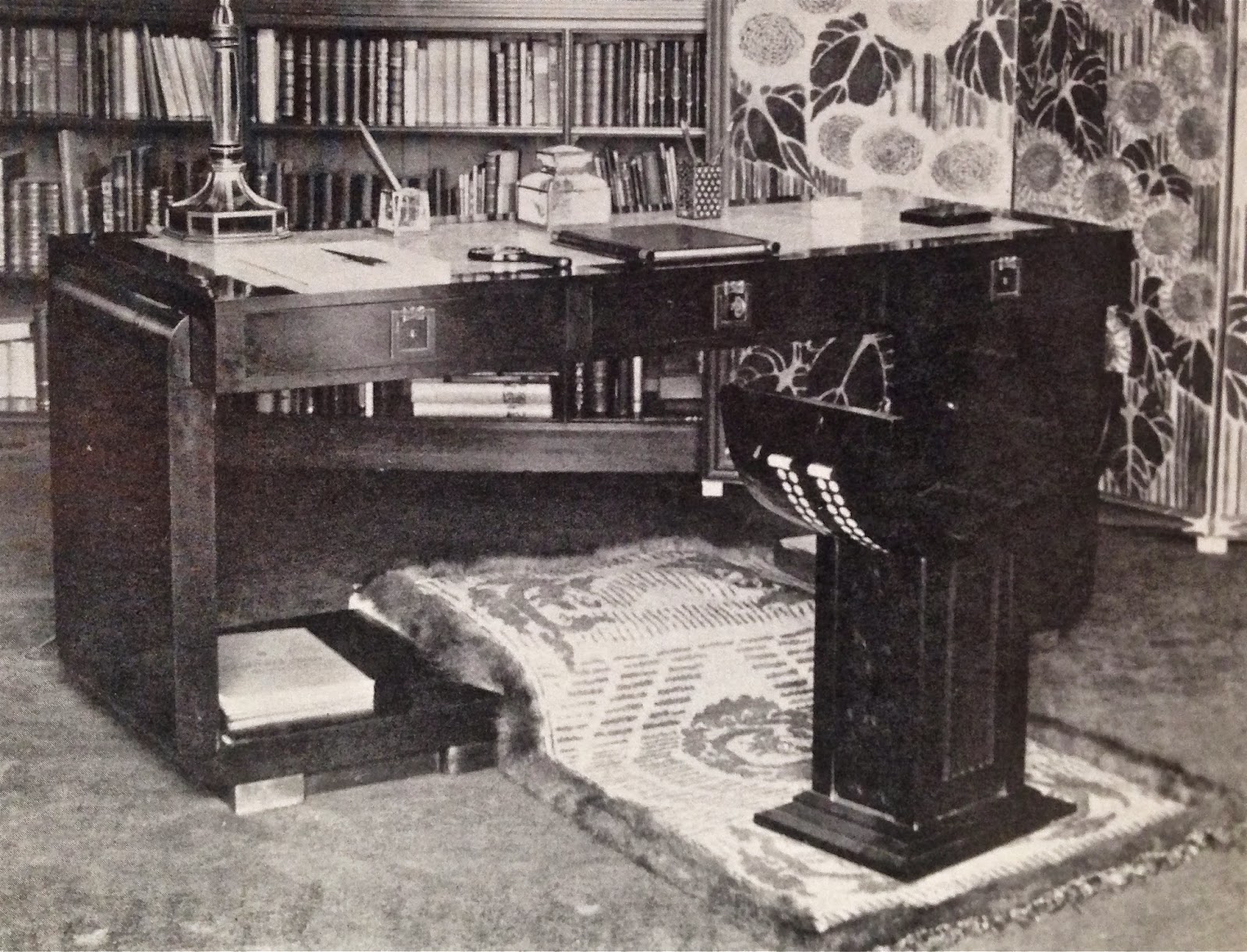

In 1928, Doucet shifted his energies to 33 rue Saint-James, a home in the suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine owned by his wife, Jeanne Roger, whom he married in 1919. Doucet commissioned the architect Paul Ruaud to build an annex that would serve as his “studio.” Reached by a grand staircase designed by Joseph Csaky, the “studio” would be filled with contemporary art by Constantin Brancusi, Giorgio de Chirico, André Derain, Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, and Amadeo Modigliani. Doucet also commissioned custom-made modernist furniture by the likes of Pierre-Emile Legrain, Eileen Gray, and Paul Iribe. Doucet died of a heart attack in 1929, shortly after the completion of the space.

Following Doucet’s death, his widow and his sister, Marie Dubrujeaud (née Doucet), gradually dispersed the collection through private and public sales and donations to French museums. Several works by Picasso and Braque were sold through the dealer Jacques Seligmann, including “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” which was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art. In 1972, Doucet’s heirs auctioned more of his estate at Hôtel Drouot, where successful bidders included Yves Saint Laurent and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A portion of Doucet’s collection is now housed at the Musée Angladon Collection Jaques Doucet in Avignon, established by Doucet’s descendants. [4]

SOURCES

[1] Weaver, Ben. “Aesthetic Voyeurs.” The London List. September 22, 2023

https://www.thelondonlist.com/culture/aesthetic-voyeurs

[2] Juliette Trey (trans. Jennifer Donnelly) (21/03/2022), Jacques Doucet (EN) in Collectionneurs, collectifs et marchands d'art asiatique en France 1700-1939 - INHA , http://agorha.inha.fr/detail/699 (Accessed 18/02/2026)

[3] “$1,328,900 REALIZED IN ONE DAY'S SALE; Doucet Collection Breaking All Auction Records.” The New York Times. June 7, 1912

https://www.nytimes.com/1912/06/07/archives/1328900-realized-in-one-days-sale-doucet-collection-breaking-all.html

[4] Jozefacka, Anna, "Jacques Doucet (also Jacques-Antoine)," The Modern Art Index Project (February 2017), Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://doi.org/10.57011/KHUM8583

Image: Henri Rousseau, “The Snake Charmer” (1907); Sofa by Marcel Coard; Carpet by Pierre Legrain; Pablo Picasso, “Man with Guitar” (1912); Bilboquet table by Eileen Gray; Ebony cartonnier by Pierre Legrain with lacquer panels; Giorgio de Chirico, “Metaphysical Composition with Toys” (1914); Amadeo Modigliani, “The Pink Blouse” (1919); Sculptures by Modigliani and Jean Chauvin