The Collector: William N. Copley

The Collector01.29.2026

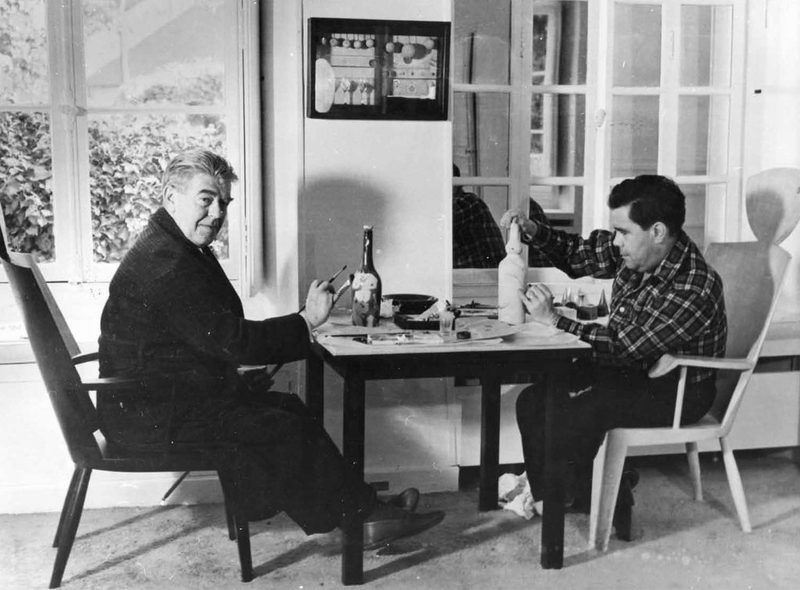

William N. Copley (1919-1996) was an art collector, writer, philanthropist, and painter, known by the artistic moniker CPLY. He assembled a prominent collection of Surrealist and Dada works through his close connections with fellow artists.

“I do not understand painters who do not collect…the urge to collect art is part of the urge to create art,” Copley once said. “Creating a good collection is like making a good painting, it should have perfect unity, it should be a statement, it can extend our experience.” [1]

Copley was born in New York. After their parents died during the 1919 Spanish Flu, he and his brother were adopted by the publishing tycoon Ira C. Copley. Copley described his upbringing as conservative and authoritarian: “I came from a family who believed that all artists are either Communists or homosexuals. Four years at Andover, four years at Yale, four years in the army…it all left me looking for something revolutionary.” [Ibid.]

He found that revolutionary something after he returned from serving in Europe during World War II. Now based in California, where he worked as a reporter for one of his father’s papers, Copley married quickly. His brother-in-law, John Ployardt, introduced him to Surrealism, which profoundly influenced Copley. “Surrealism,” Copley wrote, “made everything understandable: my genteel family, the war, and why I attended the Yale Prom without my shoes. It looked like something I might succeed at.” [2]

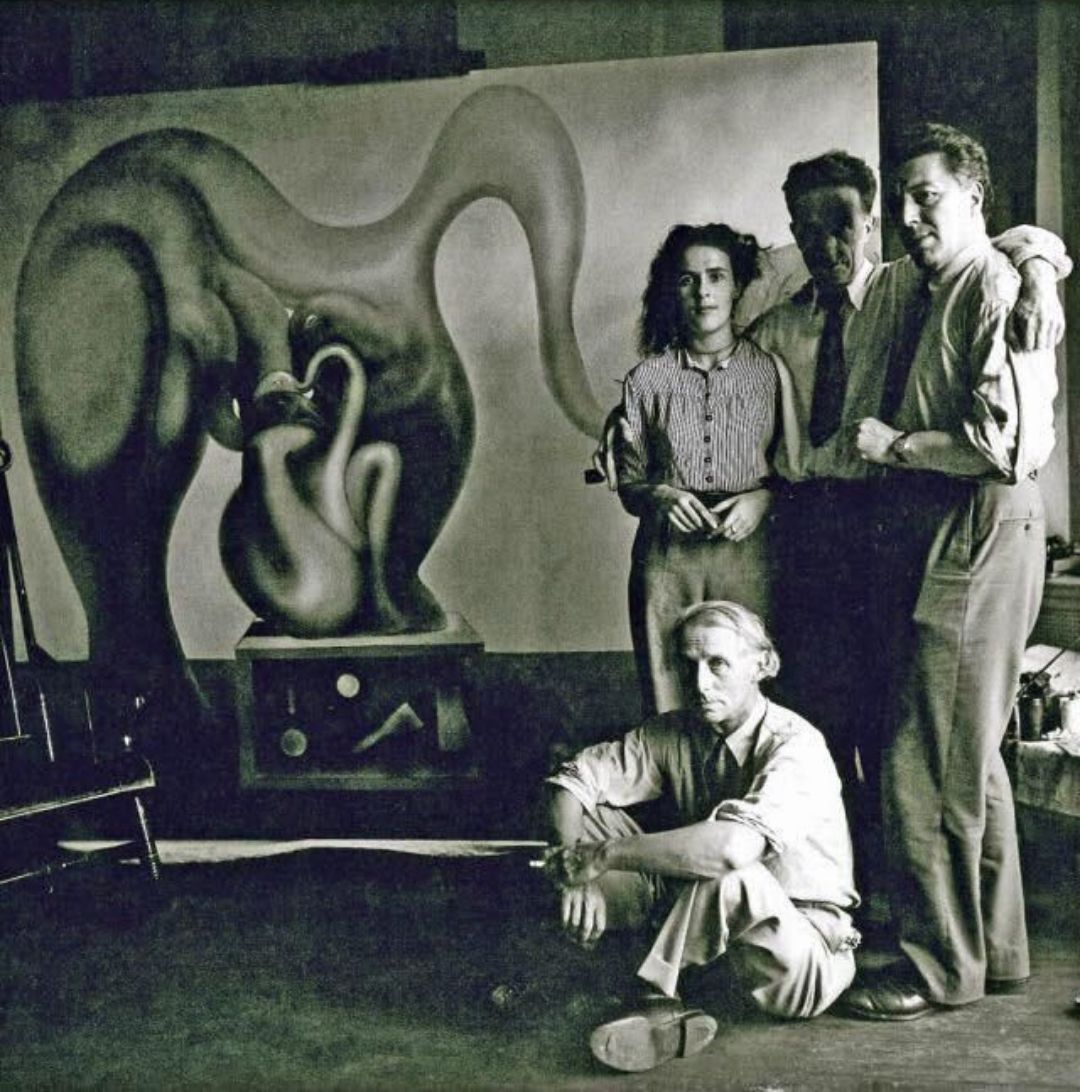

After the death of his father in 1947, Copley and Ployardt decided to open an art gallery in Los Angeles in a bungalow on 257 North Canon Drive. Together, they sought out Surrealists living in the United States, beginning with Man Ray, who was then living in Hollywood. As Copley recalled in his 1977 memoir “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dealer,” “I think he was touched by our youth and lunacy and our homage. He was suspicious though, until he realized the extent of our lunacy and the abjectness of our homage. He let us in.” [3] Man Ray referred the duo to Marcel Duchamp, who connected them to the New York dealer Alexander Iolas (who would later become Copley’s primary New York and Paris dealer). Iolas provided contacts and introduced the pair to Joseph Cornell, who agreed to show at the gallery and sold them boxes for $100 each. Finally, they went to Arizona to meet Max Ernst in Sedona, Arizona. Duchamp had wired Ernst ahead of time and put in a good word for Copley and Ployardt.

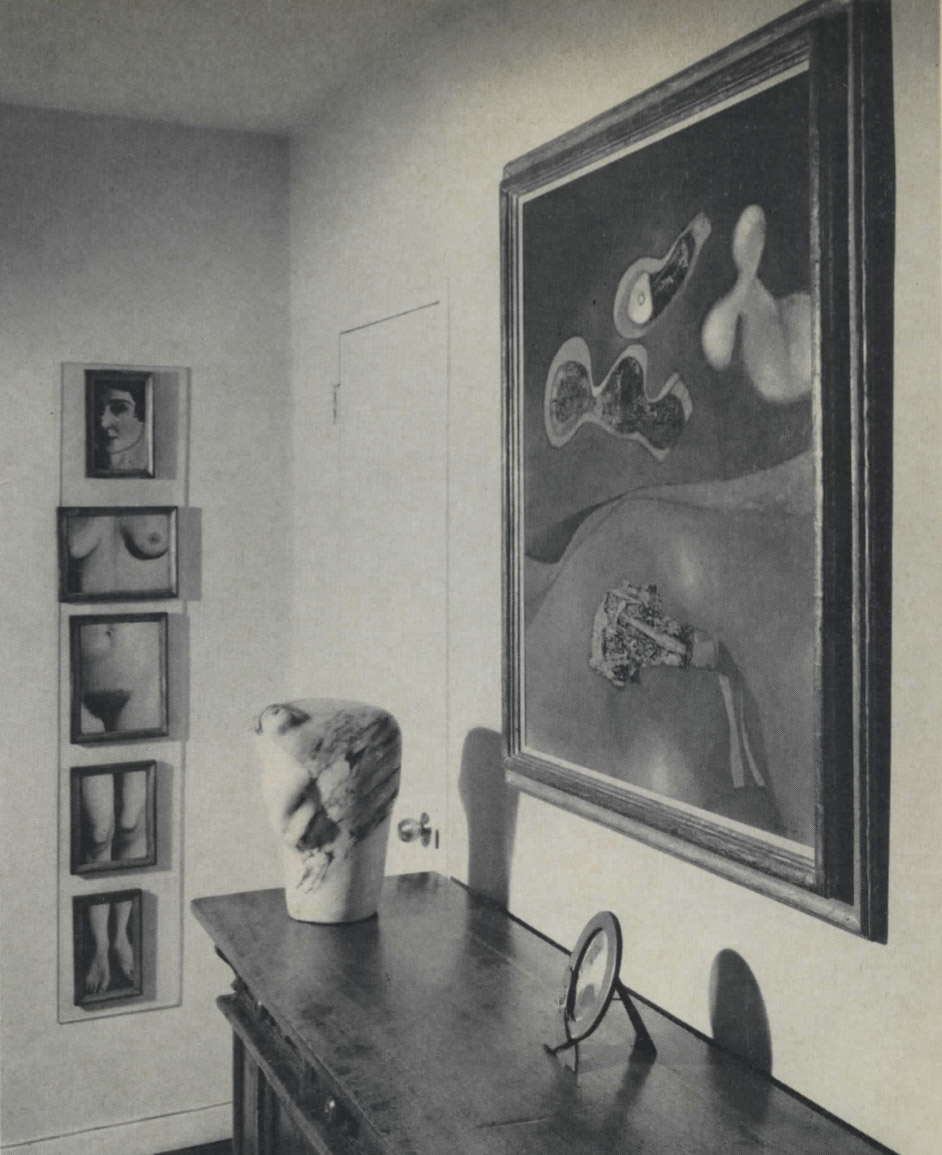

The Copley Galleries opened in 1948 and exhibited René Magritte, Cornell, Yves Tanguy, Roberto Matta Echaurren, Man Ray, and Max Ernst. It was a short-lived venture that lasted only six months, from September 1948 to February 1949; At the time, the market for Surrealist works had not yet been established stateside. But Copley’s financial naivete ultimately launched his collection; The shows undersold, and Copley acquired many of the works himself, among them Man Ray’s “A L’heure de L’Observatoire: Les Amoureux” (1932-34), Ernst’s “Le Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe” (1944), and Magritte’s “L’Évidence Éternelle” (1930). [Ibid.]

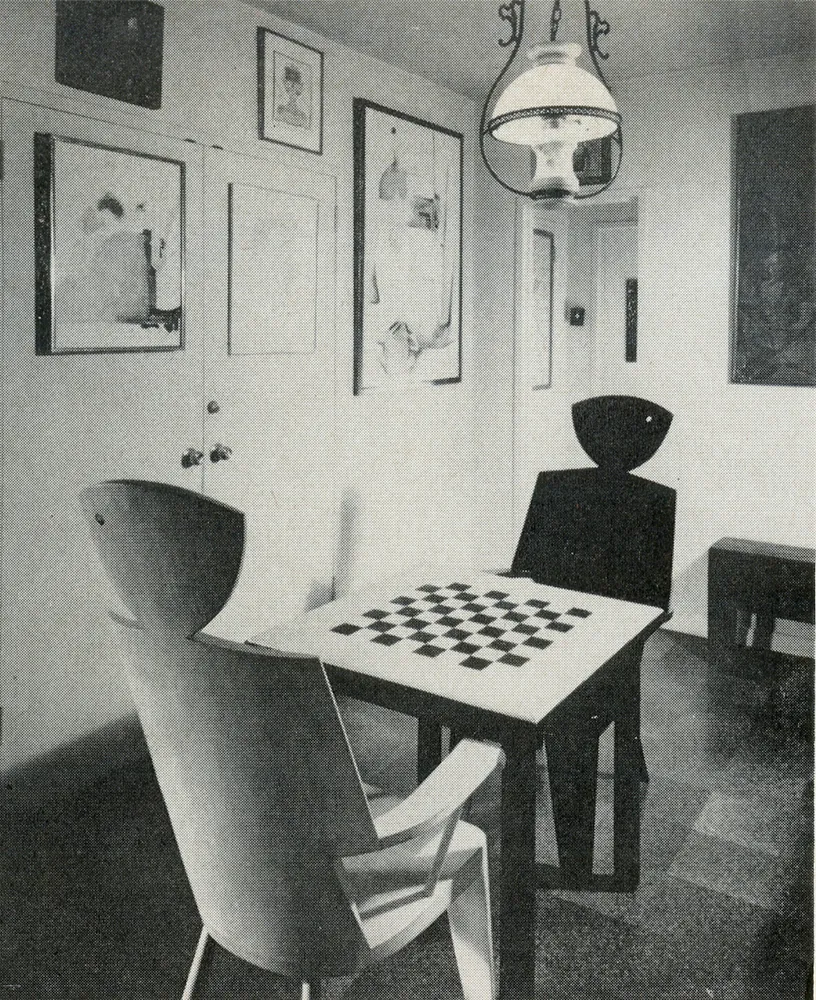

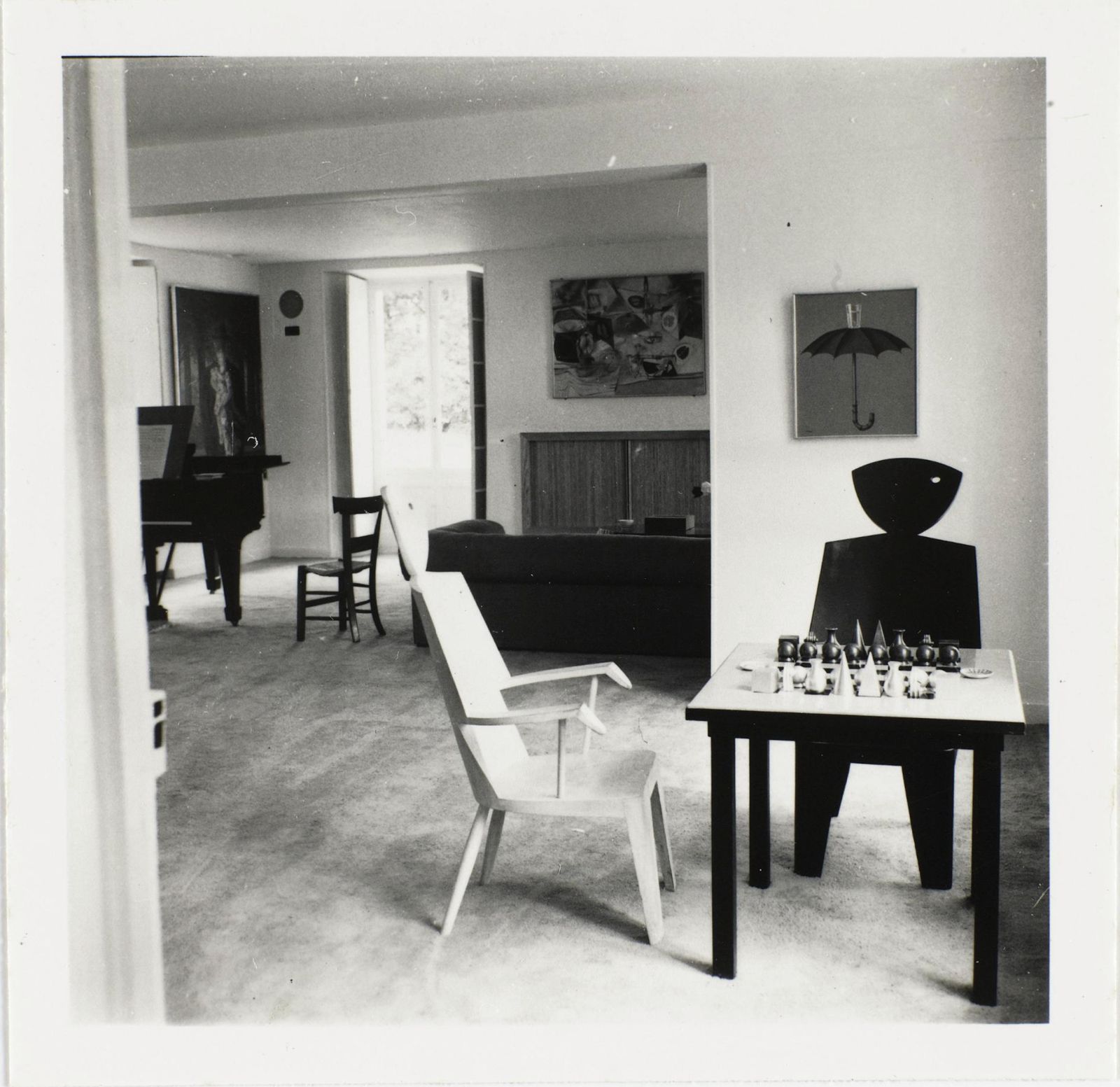

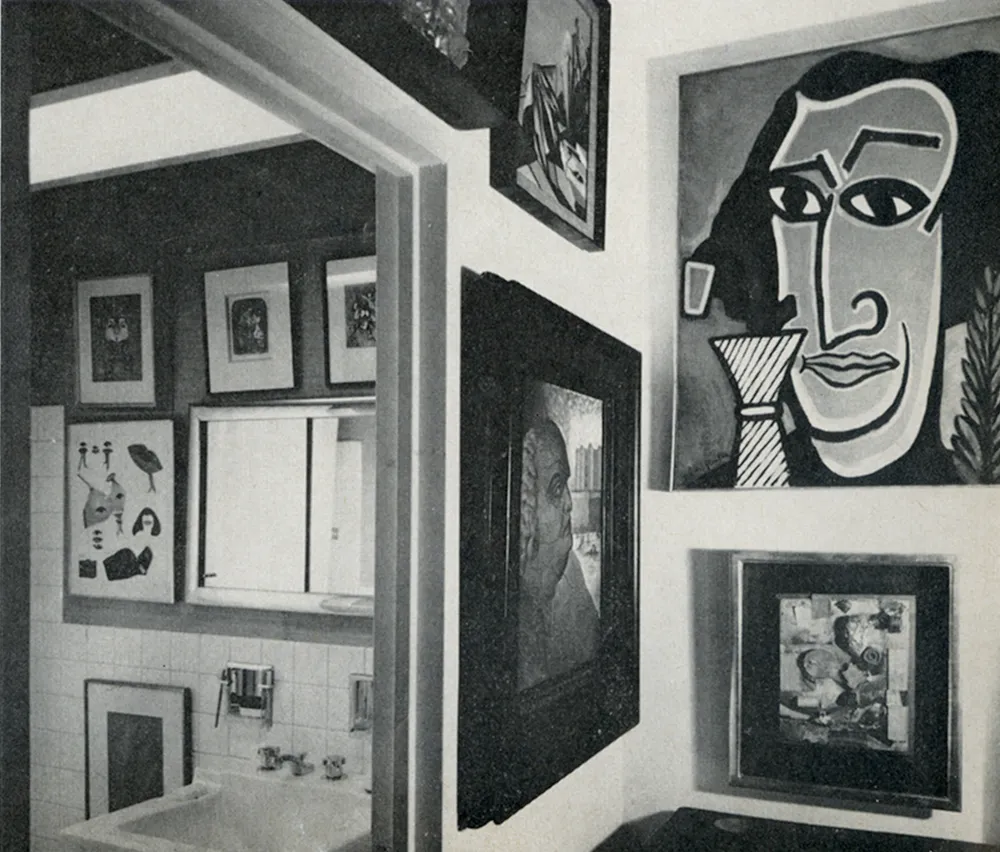

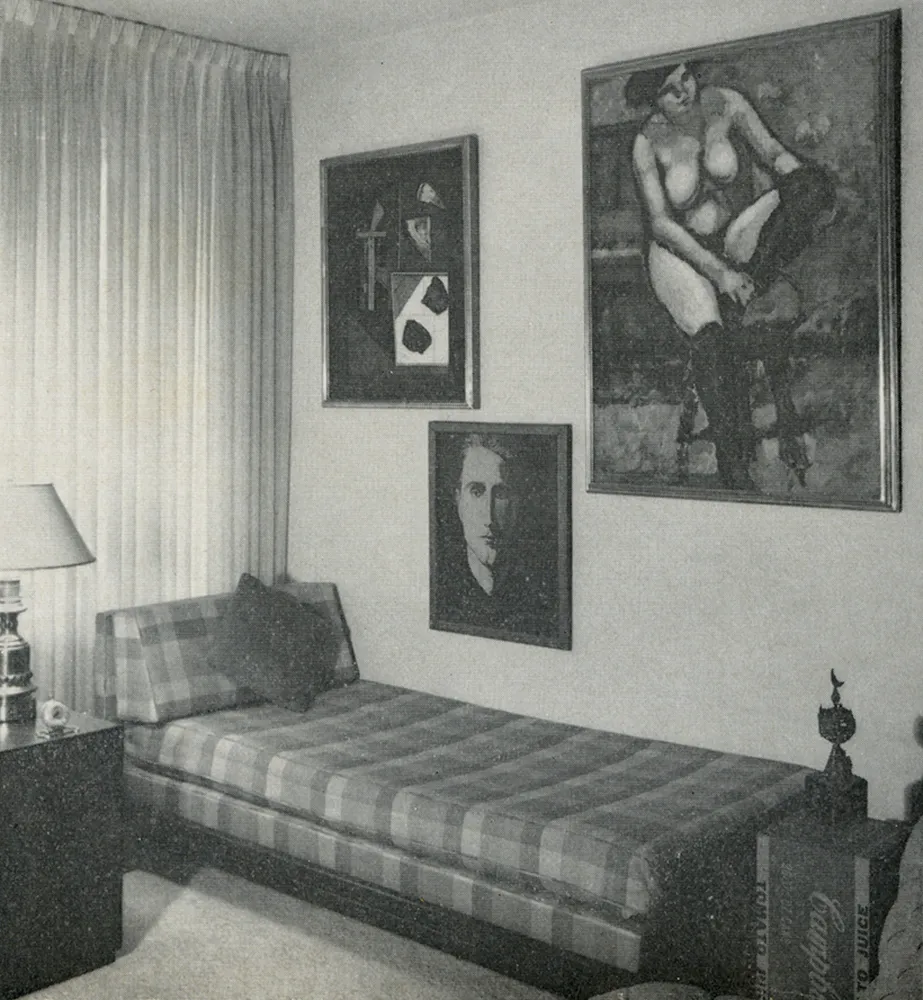

In 1951, as his marriage collapsed, Copley moved to France to concentrate on his paintings, which were brightly colored and dealt with themes of sex and humor. Copley’s friendship with the surrealists informed his collection, which included works by Hans Bellmer, Francis Picabia, Dorothea Tanning, Joan Miró, and more. Among the masterpieces were Magritte’s “La trahison des images [Ceci n'est pas une pipe]” (1929) and “La chambre d'écoute” (1952).

Man Ray introduced Copley to his second wife, Noma Copley (née Ratner), in 1951. The couple married in 1953, and the next year, they used funds from Copley’s inheritance to found the William and Noma Copley Foundation (later renamed the Cassandra Foundation in 1966). The nonprofit awarded annual grants in visual arts and music as chosen by an advisory board composed of many prominent names in modern art, including Alfred H. Barr Jr., Herbert Read, and Julian Levy, as well as artists Jean Arp, Ernst, and Man Ray. From 1960 to 1966, the Foundation published a series of monographs edited by the artist Richard Hamilton. The Foundation also facilitated the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s acquisition of Marcel Duchamp’s “Etant donnés.” [4]

“The essential element which binds me to a work of art is above all else its mystery. I always sell a painting if I begin to understand it…this infuriates me more than anything else. Once I had a Picasso painting of a girl…her eyes kept following me around the room,” Copley said. “A few weeks after I had bought it, I realized that the mobility of those eyes was based on an optical trick of complementary colors…I got rid of it immediately. Surrealist works never fail me in this manner. They invariably are based on the ambivalence of visual forms, on visual puns.” [1]

Copley returned to New York in the early 1960s. In 1968, Copley co-founded the Letter Edged in Black Press, Inc. and published six issues of SMS (“Shit Must Stop”), a collaborative portfolio that acted as an “instant art collection.” The contributors ranged from established to emerging artists, including Marcel Duchamp, Roy Lichtenstein, Yoko Ono, Christo, John Cage, Lee Lozano, La Monte Young, Bruce Nauman, and more. [4]

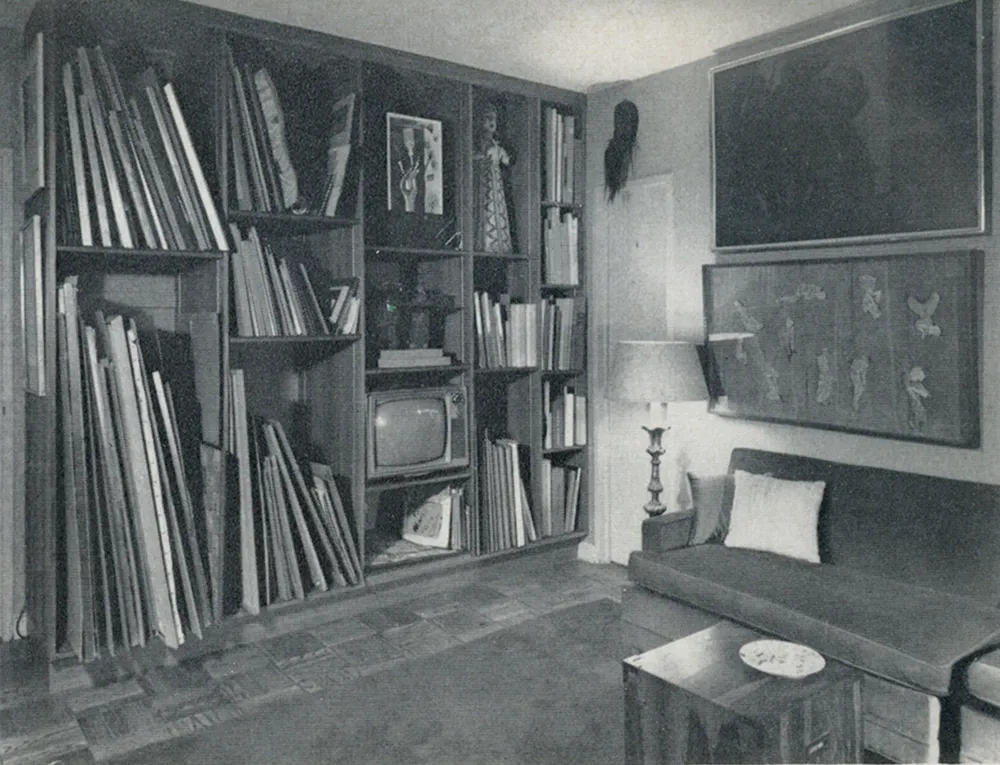

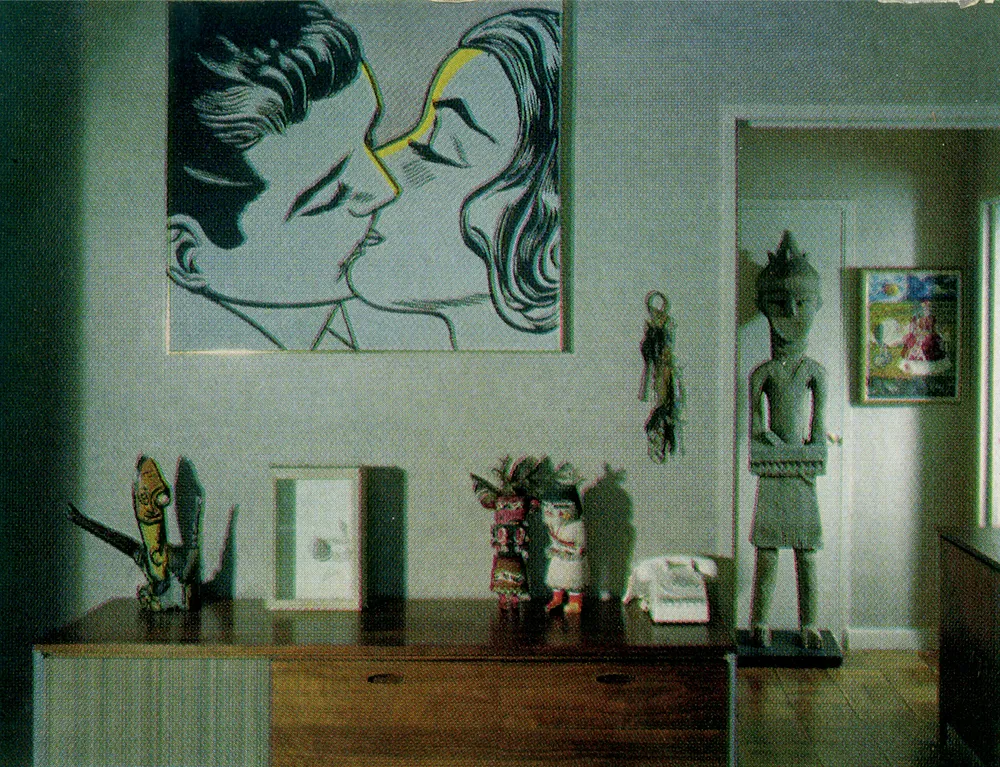

From 1964 to 1966, Marcia Tucker worked as the collection’s “amanuensis.” “I did everything…I boiled eggs. I packed suitcases. I wrote letters. I talked to them,” Tucker said. “I entertained Duchamp one day when they were away.” [5] By this point, Copley owned over 35 works by Ernst, whom he considered “the painter who has best achieved that 50-50 balance between form and humor which I seek for in art.” He had also picked up several Pop works since returning to New York, including pieces by Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg. [6]

In 1979, Copley sold much of his personal collection at Sotheby’s for $6.7 million, then a record for the sale of a single collection in the United States. Magritte’s “A L'Heure de l'Observatoire: Les Amoureux” sold for $750,000, the highest price ever paid at auction for a surrealist painting and three times the previous record for such art. The Menil family purchased seven works, including seminal pieces by Ernst, Magritte, and Jean Tinguely. In an interview with The New York Times, Copley said that he had decided to sell the collection because “these things used to be pictures and now they are embarrassingly valuable as art.” He continued, “I don't want the curatorial responsibility at this point in my life.” [7]

That said, Copley continued collecting after the Sotheby’s sale. He acquired sculptures by H.C. Westermann through the Frumkin Gallery, bought work directly from artists such as Ray Johnson and Judith Bernstein. His own gallerist in the 1980s, Phyllis Kind, sold him numerous works by Jim Nutt, Martin Johnson and Howard Finster. A second major sale of works from Copley’s collection was held in November 1993 at Christie’s East.

SOURCES

[1] Du Plessix, Francine. “William Copley, The Artist as Collector.” Art in America. December/January, 1965/66

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/from-the-archives-william-copley-the-artist-as-collector-63173/

[2] Copley, William N. “William N. Copley: Selected Writings,” edited by Anthony Atlas, Walther König, 2020.

[3] “Copley Galleries.” https://williamncopley.com/programs/copley-galleries/

[4] O'Hanlan, Sean, "William Copley," The Modern Art Index Project (August 2021), Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://doi.org/10.57011/MXQE5381

[5] Oral history interview with Marcia Tucker, 1978 August 11-September 8. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-marcia-tucker-12818#overview

[6] “Copley Collection.” https://williamncopley.com/programs/copley-collection/

[7] Reif, Rita. “Man Ray Painting Brings $750,000.” The New York Times. November 6, 1979

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/11/06/archives/man-ray-painting-brings-750000-bought-by-european-collector-other.html

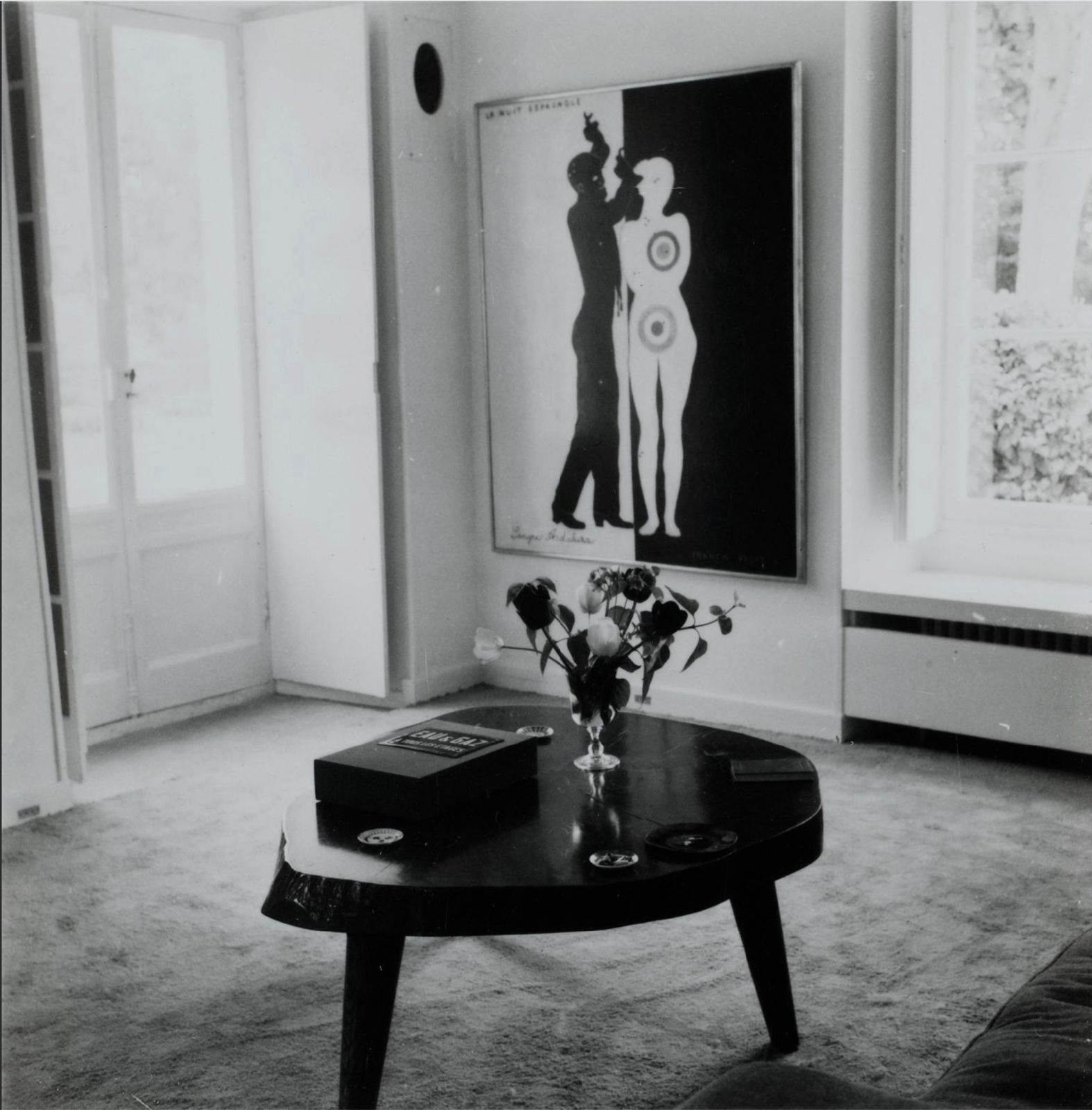

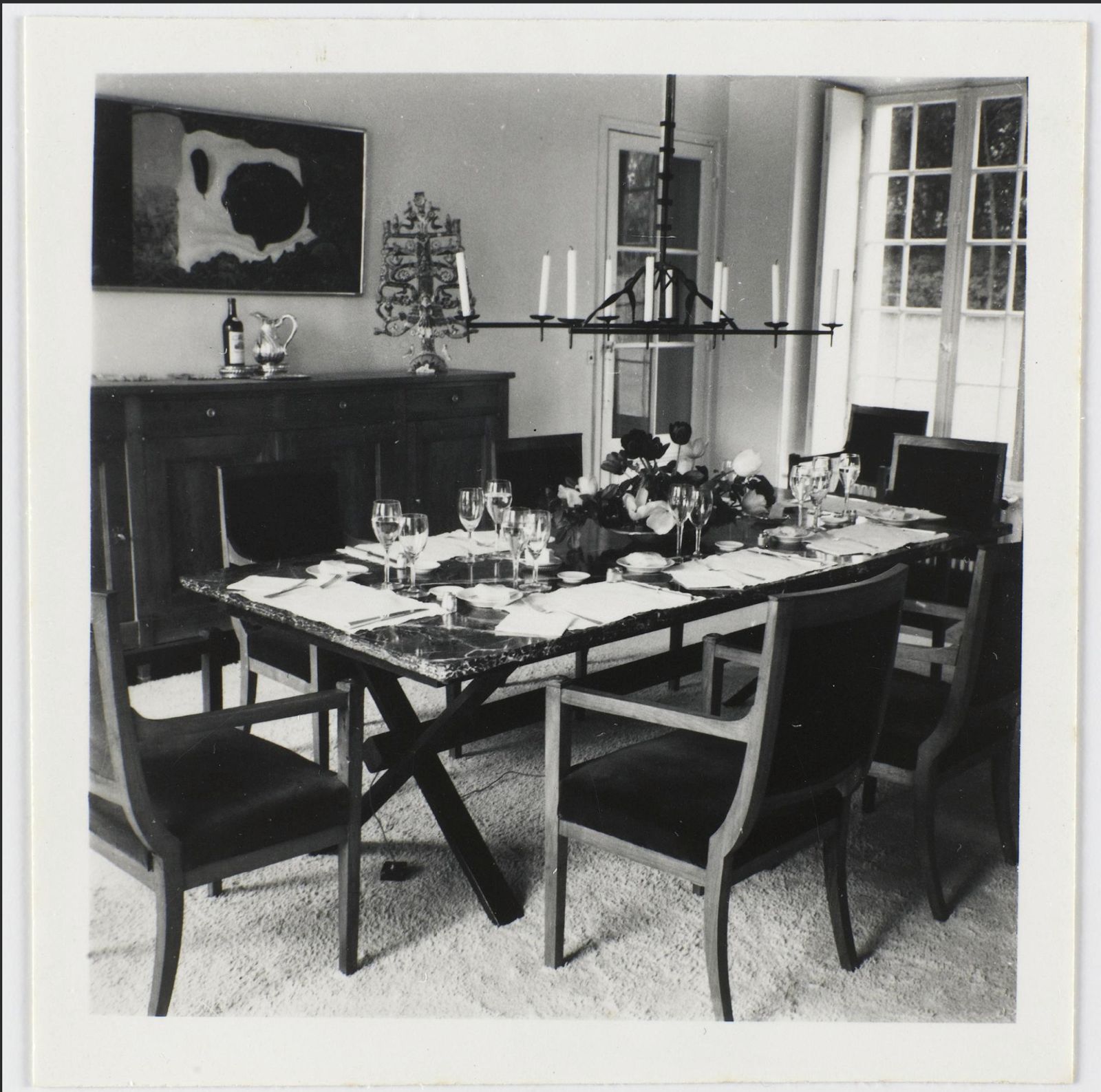

Image: A housepost from the Sepik region of New Guinea has been inverted to a horizontal position to cover a structural beam. Paintings, clockwise, are Francis Picabia, “La Nuit Espagnole” (1922) and Max Ernst, “Le Surrèalisme et La Peinture” (1942); Joan Miró, “Portrait de Madame B.” (1924); Wifredo Lam, “Cardinal Harps (Arpas Cardinales)” (1948-57). Jean Arp’s bronze, “Concrétion Humaine” (1948) is on the floor at left