The Collector: The Abrams Family

The Collector01.21.2026

The Abrams family introduced millions of readers to art through their authoritative art books and illustrated volumes. Over eight decades, the father-son duo Harry N. Abrams and Robert E. Abrams, known as Bob, amassed a collection of 20th-century artwork of the same remarkable quality and depth.

Harry was born in London and emigrated to Brooklyn in 1912, where the family lived in the back of his father’s shoe store. After dropping out of high school to work at the family business, Harry attended the National Academy of Art, “because my mother felt I should not remain in the shoe business and thought I could become an artist,” he would say. Later, he studied at the Art Students League of New York but left and “decided to get a job with an art service where I could learn to do commercial illustration and lettering, for I knew I would never measure up to being a fine artist.” [1] He found a job at Sackheim & Scherman, an advertising agency that serviced book publishers. In 1936, he joined Harry Scherman’s Book-of-the-Month Club as art director.

By the late 1940s, Harry was itching to start his own publishing house, and in 1949 he founded Harry N. Abrams, Inc, the first company in the U.S. to specialize in art books. At the time, the only companies that specialized in art books with color plates were in Europe. Only Skira, founded in 1928, had plans for distribution in the United States. Abrams borrowed the European format for his books: a biographical introduction and fifty tipped-in color plates, with commentary facing each work. Its first three titles were books on Renoir, Van Gogh, and El Greco, which inaugurated the Library of Great Painters series. Clement Greenberg wrote that Meyer Schapiro’s “Van Gogh” was “as penetrating an analysis of Van Gogh’s art and development as I have yet seen.” [2]

Other successful titles included H.W. Janson’s “History of Art” and Thomas S. Buechner’s “Norman Rockwell: Artist and Illustrator.” “I ran into some flack about the wisdom of a ‘serious’ art book publisher bringing out a volume on Rockwell,” Harry would recall. “I’d like to think that as well as bringing pleasure to thousands of Rockwell’s admirers, the book also accomplished one of Thomas Buechner’s objectives: ‘that illustration should be considered an aspect of the fine arts.’” [1]

Harry started collecting art in the 1930s, purchasing paintings by art school friends and artists with day jobs in commercial illustration. His first serious acquisition was by Futurist David Burliuk, and he also collected the American Realists of the 1930s (Thomas Hart Benton, Raphael Soyer, Philip Evergood) and modern European masters (Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet). “I liked collecting paintings, and I was becoming more and more involved. And so, as I earned more money I bought art at every opportunity. I didn’t ever expect to have as large a collection as we have today. I had the bug and I couldn’t seem to stop.” [Ibid.]

Harry’s collecting habits were rocked by Sidney Janis’ groundbreaking exhibition of Pop Art, the International Exhibition of the New Realists, which was held in a space opposite the Abrams office on 57th Street. “I dropped in to see it one day on my way to lunch and, I remember, my first reaction was derision and laughter. But two days later I went back and looked again, and I became more serious,” Harry said. “On following days when I returned I had become deeply impressed—never had I changed my mind so quickly from a completely negative response to one of great enthusiasm, and it was at that point that I started to buy Pop Art.” [Ibid.]

That experience caused him to pursue the big names in American pop, including Tom Wesselmann, Jim Dine, and Andy Warhol—artists whom he also befriended. One especially memorable piece of Abrams family lore involves Warhol bringing Bob and his brother Michael on an adventure to Times Square. The artist directed the teenagers inside a photobooth and fed it $5 worth of quarters. He would later turn one striking shot of the brothers into a trio of silkscreen portraits for Harry. [3]

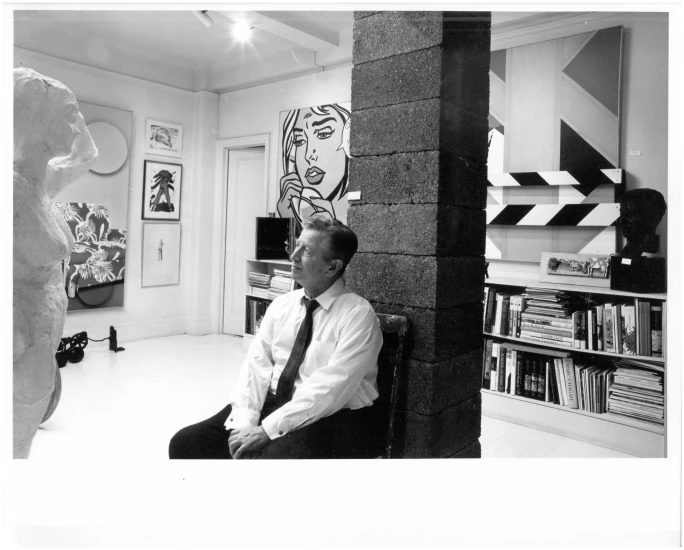

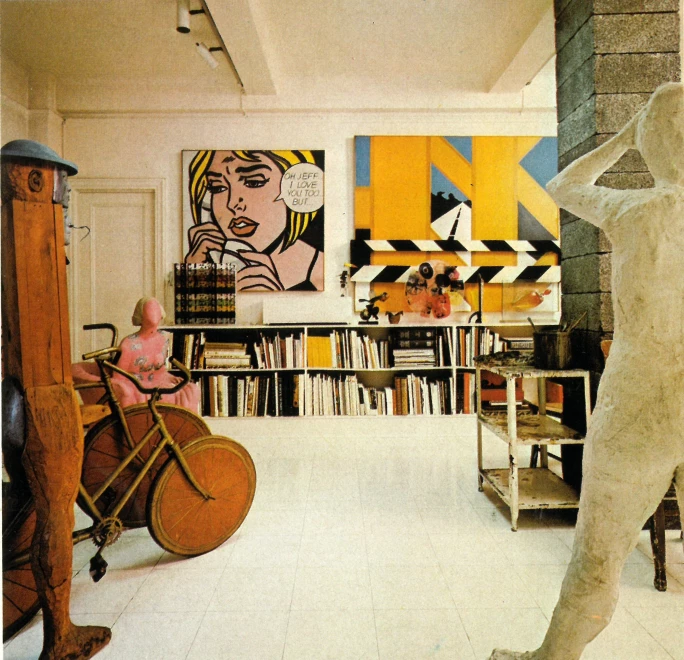

Harry’s public identity as a publisher and collector was intertwined. A 1965 profile in “Life” magazine shows him amongst works by Wesselmann, Gerald Laing and Marisol. [4] His collection was celebrated in a 1966 exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York, and included masters like Picasso, Henry Moore, and Rockwell, in addition to work made and purchased in the previous three or four years. He notably missed out on the Abstract Expressionists. “I understood them too late,” he said, “and couldn't afford them when I finally did.” [5]

Harry sold his eponymous company in 1966 (which continues today as Abrams Books), but stayed on for some years as chairman and CEO. In 1977, he partnered with Bob to launch a new art book publishing house called Abbeville Press, which is still in operation today. When his father died two years later, Bob inherited his father’s company and art collection.

Bob made his mark on the family business with luxuriously illustrated volumes like “The Vatican Frescoes of Michelangelo” (1980) and a facsimile of John James Audubon’s “Birds of America” (1985). He also followed in his father’s footsteps by forming friendships with artists and publishing monographs about artists in the family’s collection.

Bob and his wife, Cynthia Vance Abrams, lived alongside their art in a Hudson Valley home inspired by Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Guests to the “Art Barn” were greeted with works by Wesselmann, Fernando Botero, Frank Stella, George Segal, Alex Katz, Christo, and many more. The centerpiece was Isamu Noguchi’s “Study for Energy Void” (1971), a torqued sculpture whose form and concept characterize the artist’s practice. Noguchi created three sculptures bearing this trapezoidal form, but the Abramses’ piece, purchased directly from the artist by Bob in 1979, is the only one made of marble.

SOURCES

[1] Oral history interview with Harry N. Abrams, 1972 March 14. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-harry-n-abrams-13015

[2] Greenberg, Clement. “Realism and Beyond.” The New York Times. December 3, 1950

https://www.nytimes.com/1950/12/03/archives/realism-and-beyond-among-the-moderns.html

[3] Ebony, David. “Art Without Boundaries.” Sotheby’s. August 29, 2024

https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/art-without-boundaries

[4] Dafoe, Taylor. “Noguchi And Marisol Sculptures Lead Sale Of Storied Abrams Family Collection.” The Art Newspaper. August 27, 2024 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/08/27/noguchi-and-marisol-sculptures-sale-abrams-family-Sothebys

[5] Lask, Thomas. “Harry N. Abrams, Publisher, Dies; A Pioneer With Quality Art Books.” The New York Times. November 27, 1979 https://www.nytimes.com/1979/11/27/archives/harry-n-abrams-publisher-dies-a-pioneer-with-quality-art-books.html

Image: Alex Katz, “Joan” (1974)