The Collectors: Virginia and Bagley Wright

The Collector02.11.2026

How many outdoor works of art can you buy with $1 million? This was the question posed to Virginia Wright in the late 1960s. Alongside her husband, Bagley, the Wrights reshaped the artistic landscape of Washington and were crucial in the expansion of the Seattle Art Museum for over half a century.

Known as Jinny, Virginia Wright was born in Seattle on January 1, 1929, to Prentice Bloedel and Virginia Merrill Bloedel. The family would move to Vancouver and amass a fortune in the lumber industry. As a child, Wright expressed an interest in drawing, but she was otherwise not exposed to much art, saying, “Museums were not a part of my life in growing up.” [1]

It wasn’t until she went to boarding school in Dobbs Ferry, New York, that she began visiting world-class museums like the Frick Collection on school trips into Manhattan. After two years at the University of British Columbia, Wright transferred to Barnard College, where a friend encouraged her to study with art historian Meyer Schapiro at Columbia. Wright likened Schapiro’s lectures to “the conversion of St. Paul,” particularly in the way that it affected her thinking of contemporary art. “He showed how modern art really had its roots in the 19th Century and made a logical case that this was—what we were seeing in the ’50s was a direct development that went far back in our history.” [Ibid.]

After graduating from Barnard in 1951, Wright worked at Sidney Janis Gallery until 1954. She had a front row seat to the emerging Abstract Expressionist scene and made her first major art purchase, Mark Rothko’s “#10” (1952), from the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1953. “It was $1,000, the painting,” Wright recalled. “And so, I went to Betty, and she said, ‘No. Rothko doesn't sell like that. I mean, you'll have to be interviewed.’” The artist turned out to be “very nice and kind” and allowed Wright to buy the work, with two stipulations: that the painting should be displayed in any size dwelling, even Wright’s small apartment, and that the painting could not be lent to the MoMA for at least a year. [Ibid.]

In 1951, while working at Sidney Janis, Wright met her future husband, C. Bagley Wright, a journalist. They married in 1953 and would have four children together. The couple relocated to Seattle in 1955 and found a “cultural dustbin,” as Virginia once said. [2] She became a docent for the Seattle Art Museum in the late 1950s, leading tours, giving lectures, and teaching art appreciation courses. While the SAM owned several works by contemporary northwest artists like Mark Tobey, Guy Anderson, Kenneth Callahan, and Morris Graves, the museum’s founder and director, Richard Fuller, was more interested in collecting Japanese Netsuke miniatures. But, as Wright said, “he was smart enough to see that a museum needed to encompass contemporary art as well as historic.” [1] In 1959, the Wrights made their first-ever gift to SAM’s collection, William Ward Corley’s “Room with White Table” (1953) and also provided funding for SAM to acquire “Winter’s Leaves of the Winter of 1944” (then titled “Leaves Before Autumn Wind”) by Graves.

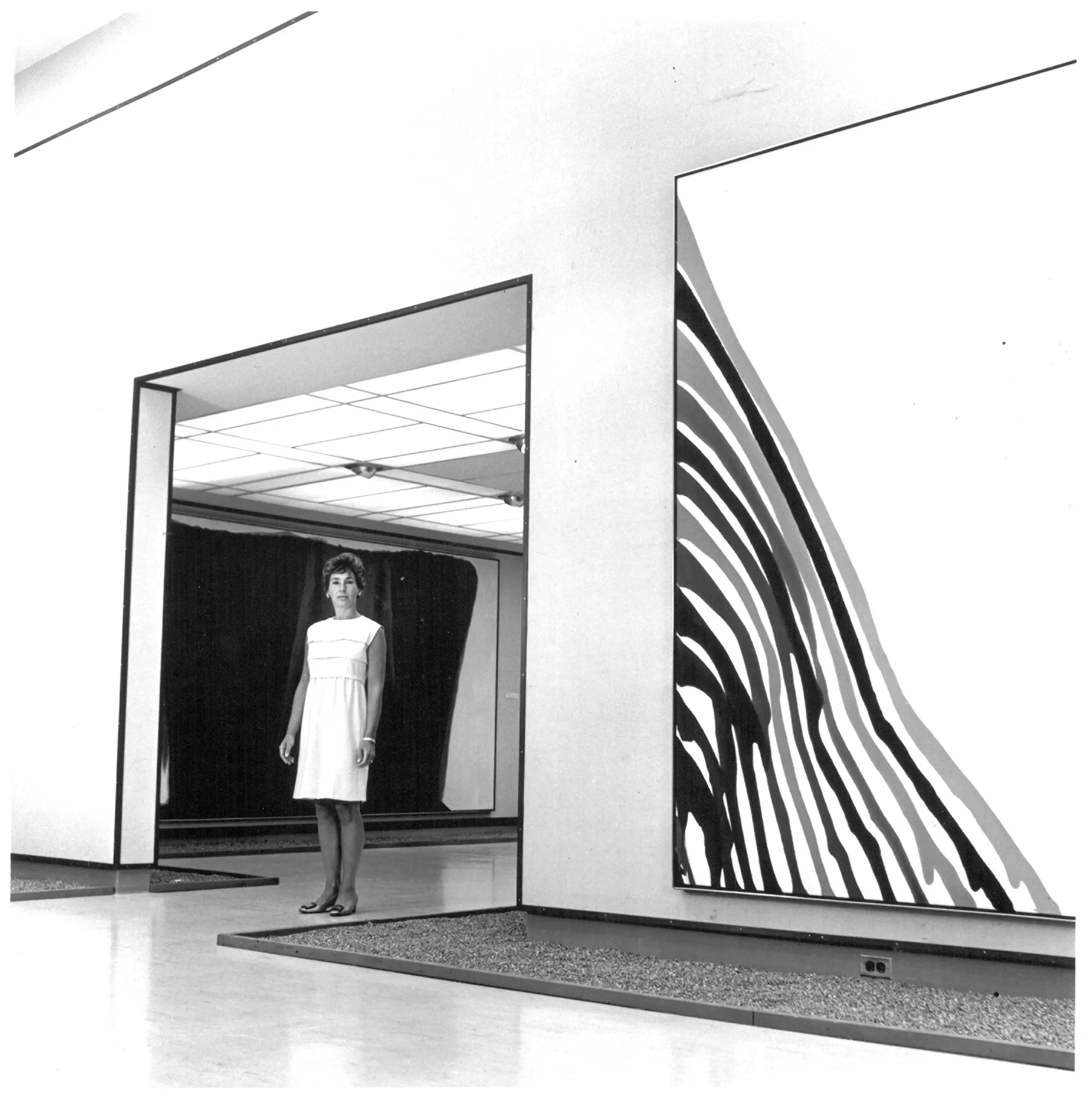

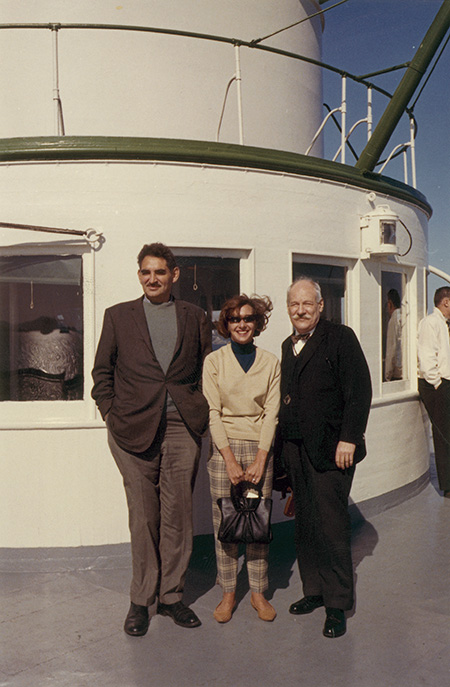

The 1962 World’s Fair was a turning point for the museum and the Wrights. Bagley, now a real estate developer, helped develop the iconic Space Needle, while Virginia helped organize a contemporary art exhibition at the fairgrounds. “After the World’s Fair, Seattle stopped being so parochial,” Virginia said, and a group of local collectors felt emboldened. [3] According to Wright, “We went to Dr. Fuller and said, ‘If we raise the money each year, can we then determine what contemporary art shows will come to Seattle? And amazingly he said yes!” [1] In 1964, Wright co-founded the Contemporary Art Council (CAC), which functioned as the museum’s first modern art department, sponsoring lectures and supporting groundbreaking exhibitions like 1969’s “557,087.” Titled after the population of Seattle and curated by Lucy Lippard, it is regarded as the first large-scale show of conceptual art. [4]

As both a donor and a board member, Wright worked with the SAM for six decades. She served as President of SAM’s Board of Trustees from 1986–1992, a period marked by expansion as the museum moved into a new downtown location, recruited Patterson Sims from the Whitney Museum to act as the Associate Director for Art and Exhibitions and Curator of Modern Art, and boosted its endowment to over $100 million. In 1968, Wright opened her own art gallery in Seattle, Current Editions, which ran until 1975 and focused on prints. [5]

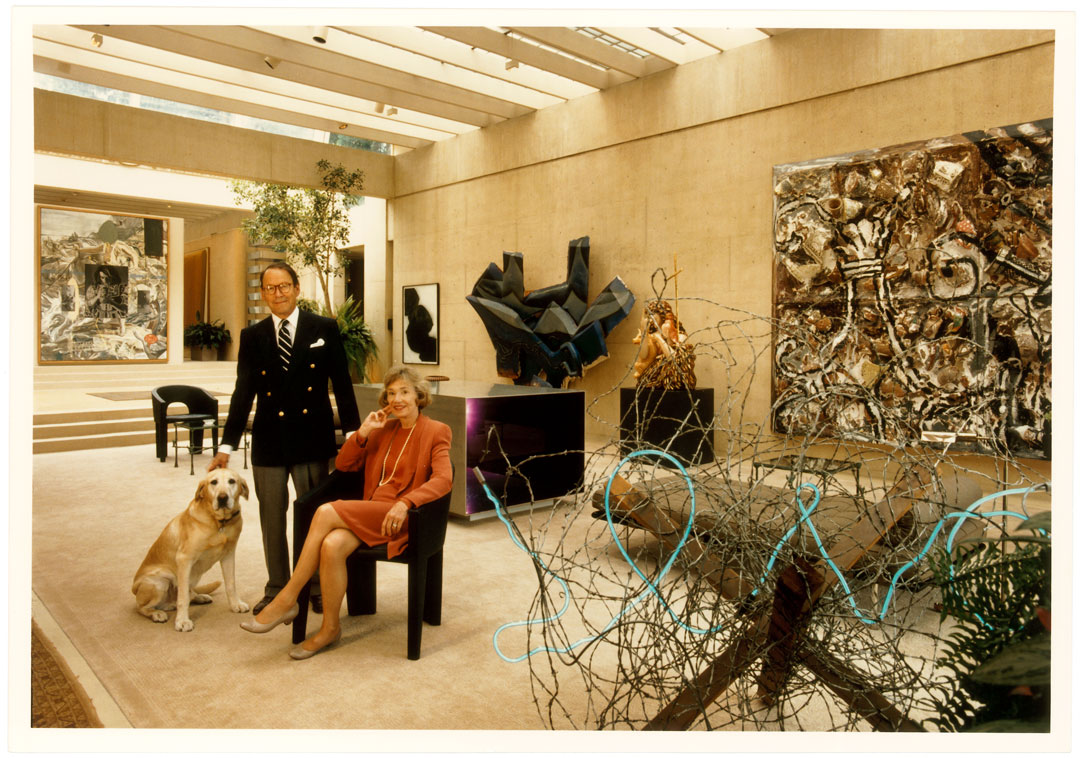

The Wright's own art collection spanned Pop, New Realism, Assemblage, Hard Edge, Color Field, and more. Virginia sought advice from gallerists like André Emmerich and Richard Bellamy and art critic Clement Greenberg. Later in her life, Virginia regretted selling or gifting Pop works like Roy Lichtenstein's “Drowning Girl, which went to MoMA. “Clem Greenberg had an inordinate amount of influence on us at a certain time,” she said. “I think he brainwashed us.” [1] In 1969, SAM hosted its first exhibition of the collection, “The Virginia and Bagley Wright Collection: Artists of the Sixties.”

That same year, Virginia’s father gave her a million-dollar endowment and instructions to buy public artworks for the region. The Virginia Wright Fund’s first purchase was Barnett Newman’s 26-foot-tall, Cor-Ten steel “Broken Obelisk,” now displayed in the University of Washington’s Red Square in Seattle. The fund contributed funds to commissions like Richard Serra’s “Wright’s Triangle” and Mark diSuvero’s “For Handel,” both at Western Washington University in Bellingham. [6]

Wright’s philanthropic efforts were plentiful. In 1976, she founded the Washington Art Consortium, a coalition of seven art museums in Washington State that strategically used funding from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The member institutions jointly owned a collection of American works on paper and photography. When it was disbanded in 2017, it had grown to include over 400 works of 20th-century American art and a $2.3 million endowment, which was divided among its members. [5]

During the same period, Wright was working with Seattle Art Commission, the NEA, and other sources to fund Seattle’s 1976 acquisition of Michael Heizer’s “Adjacent, Against, Upon,” the monumental stone and concrete sculpture sited at Myrtle Edwards Park on the Seattle waterfront. It is located near the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park, which opened in 2007 and features works from the Wrights’ collection, including Mark di Suvero’s “Bunyon’s Chess” (1965) and “Schubert Sonata” (1992), as well as works by Ellsworth Kelly, Tony Smith, Anthony Caro, and Roxy Paine. [6] “Bunyon’s Chess” was the artist’s first private commission, and the Wrights were inspired by his interactive, kinetic piece “Love Makes the World Go 'Round” (1963). Di Suvero incorporated a swing into the massive cedar and aluminum structure, but he later wrote and said, “Take it down, it's too dangerous.” [1]

In 1999, Virginia opened the Wright Exhibition Space, a free venue that showed selections from the couple’s collection. But “It was not about our collection,” Wright said when asked about opening the space. “It was about me playing curator.” [1] When the venue closed in 2014, the remaining works from the collection were donated to SAM. Over the years, the Wrights gave SAM works by Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Sigmar Polke, Frank Stella, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Agnes Martin, Eva Hesse, Robert Morris, Anselm Kiefer, and many others. Works from the Wright collection continue to be exhibited in SAM’s ongoing exhibition “Big Picture: Art After 1945,” which first opened in 2016. [7]

SOURCES

[1] Oral history interview with Virginia Wright, 2017 March 22- 23. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-virginia-wright-17481#transcript

[2] Sillman, Marcie. “Seattle arts patron Virginia Wright dies.” NPR. February 19, 2020

https://www.kuow.org/stories/seattle-arts-patron-virginia-wright-dies

[3] Appelo, Tim. “Seattle goes boom: The Seattle Art Museum becomes a mecca for American art.” Antiques. January 31, 2009

https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/seattle-goes-boom/

[4] Halper, Vicki. “Seattle Art Scene: From Century 21 to the Seattle Art Museum.” HistoryLink. April 18, 2022.

https://www.historylink.org/file/22437

[5] Durón, Maximilíano. “Virginia Wright, Prominent Collector Who Formed a Pillar of Seattle’s Art Scene, Is Dead at 91.” Artnews. February 20, 2020

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/virginia-wright-dead-91-1202678510/

[6] Farr, Sheila. “Artistic Gifts.” Window. Spring 2012.

https://window.wwu.edu/artistic-gifts

[7] Werner-Jatzke, Chelsea. “A Modern Champion: Virginia Wright (1929–2020).” February 19, 2020

https://samblog.seattleartmuseum.org/2020/02/virginia-wright/

Contemporary photos by Erik Johnson

Image: Franz Kline, “Cross Section” (1956); Philip Guston, “Untitled” (1954)