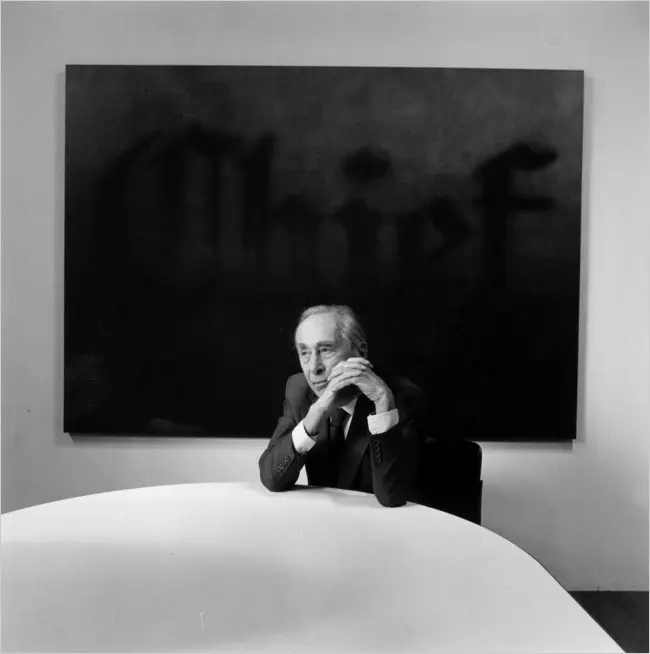

The Dealer: Leo Castelli

The Dealer10.27.2025

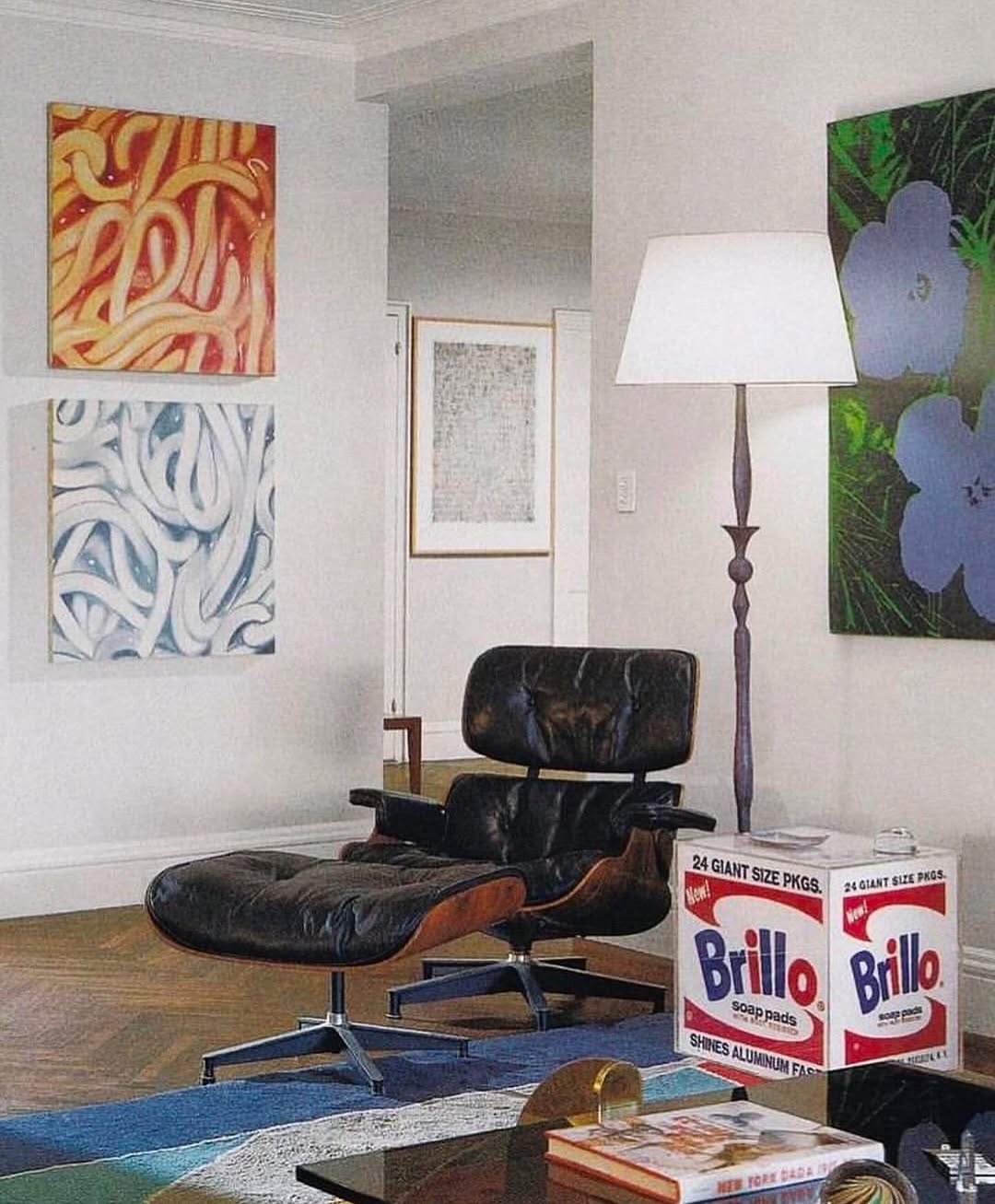

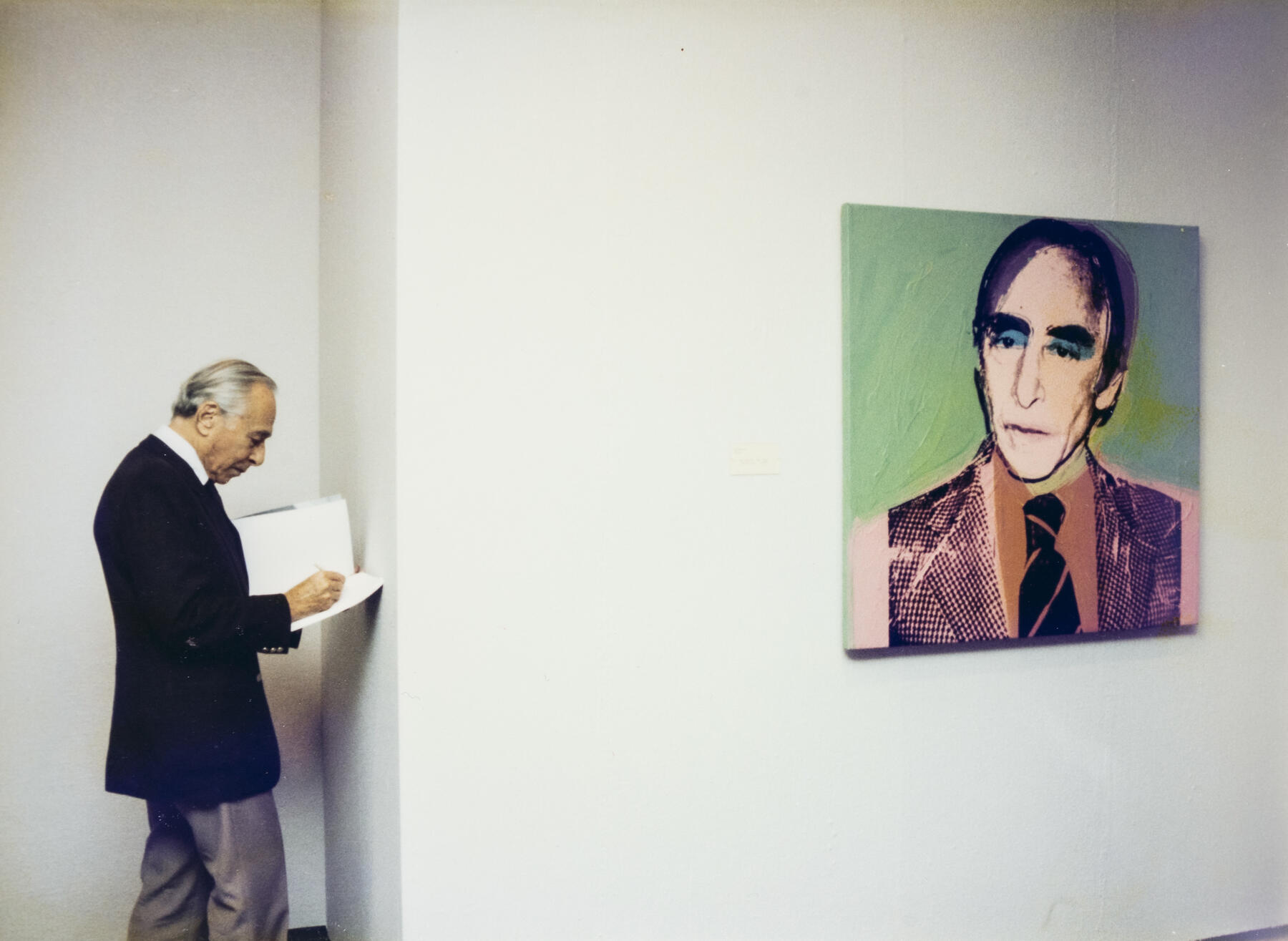

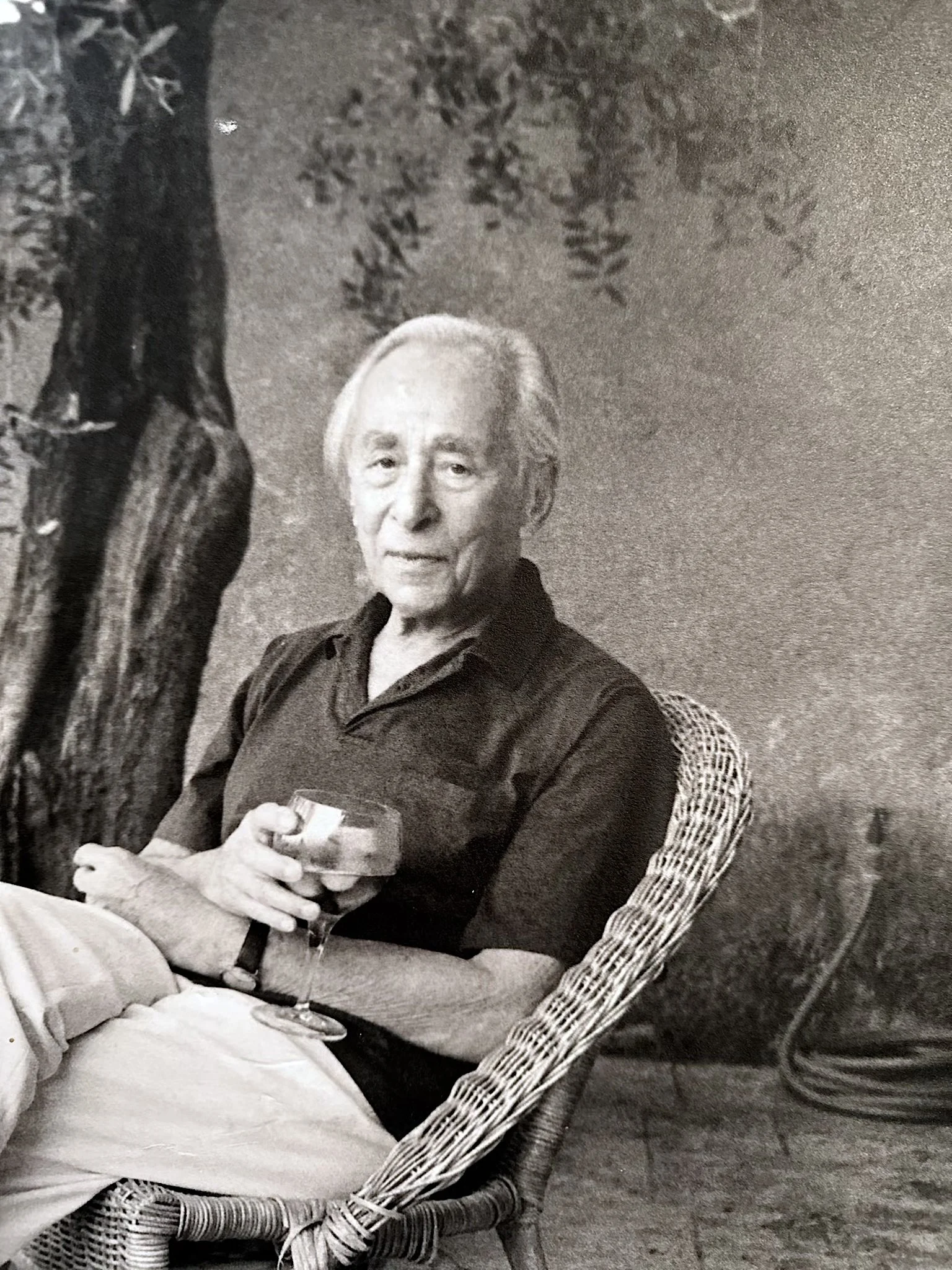

Leo Castelli’s gallery revolutionized the American art market, but his own collecting remained inseparable from his dealer practice. “I’m not even an acquirer, really,” he once said. “I simply like to have good paintings around.” [1]

Castelli was born Leo Krausz in 1907 in Trieste, then still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After studying law, Castelli was working for an insurance company in Bucharest when he met his first wife, Ileana Shapira. [2] On the couple’s honeymoon, they bought their first artwork, a Matisse watercolor. In 1935, his father-in-law, one of the wealthiest men in Romania, helped him get a banking job in Paris. There, alongside interior designer René Drouin, Castelli opened a gallery at Place Vendôme, right between the Ritz hotel and a Schiaparelli boutique. Years later, Castelli admitted that the business partners “had very mild knowledge of modern art. My main interest at that time was really literature.” [3] Funded by Castelli’s father-in-law, the Drouin Gallery opened in 1939 with a show featuring Surrealist paintings and furniture. Several months later, at the beginning of World War II, the Jewish Castellis fled France and eventually landed in New York in 1941.

In 1945, while on leave from the U.S. Army in Paris, Castelli visited Drouin’s reopened Place Vendôme gallery, which was now working with European avant-garde artists like Jean Dubuffet and Jean Fautrier. Castelli began to serve as the Drouin Gallery’s New York representative; Drouin would frequently send him Kandinskys, many of which were sold to Baroness Hilla von Rebay of the Guggenheim. [4]

At the same time, Castelli became enmeshed in Manhattan’s burgeoning art scene, befriending dealers (Sidney Janis), critics (Clement Greenberg), and emerging stars (Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning). Castelli was among the non-artists associated with The Club, the legendary discussion group inspired by Parisian salons. Through his connections with The Club, Castelli curated his 1951 breakout, The Ninth Street Show. Held in a vacant storefront, the show featured up-and-comers like de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Pollock, and announced the “coming out” of Abstract Expressionism and the New York School.

In 1957, Castelli transformed his Upper East Side townhouse into an eponymous gallery. The family continued to live in the fourth-floor apartment at 4 E. 77th Street between Madison and Fifth Avenues. “There was no living room, no dining room, nothing else. That was all,” Castelli recalled in 1969. “Well, one didn't eat there very much. It was good enough for breakfast, and the life that we led then was entirely Bohemian.” [5] The gallery’s early efforts contrasted European and American modernism, hanging a Pollock next to a Delaunay.

While Castelli remained friendly with the Abstract Expressionists, he wanted to work with emerging artists. At the urging of Robert Rauschenberg, Castelli visited the studio of Jasper Johns. It was a transformative meeting for both, with Castelli calling it an “epiphany.” [6] Johns’ first solo show at Castelli Gallery opened in January 1958, and within days, Alfred H. Barr Jr. had acquired four Johns paintings for MoMA, an unprecedented sale for an unknown artist. Castelli himself bought “Target with Plaster Casts” (1955) for $1,200, which he later sold to David Geffen for $13 million. [7]

“That son-of-a-bitch, give him two beer cans and he could sell them,” de Kooning once said of Castelli. Johns promptly cast two cans of Ballantine Ale in bronze, which Castelli then sold to the collectors Ethel and Robert Scull for $960. [8]

“There are those unsuccessful Abstract Expressionists who accuse me of killing them; they blame me for their funerals,” Castelli told The New York Times in 1966. “But they were dead already. I just helped remove the bodies.” [9]

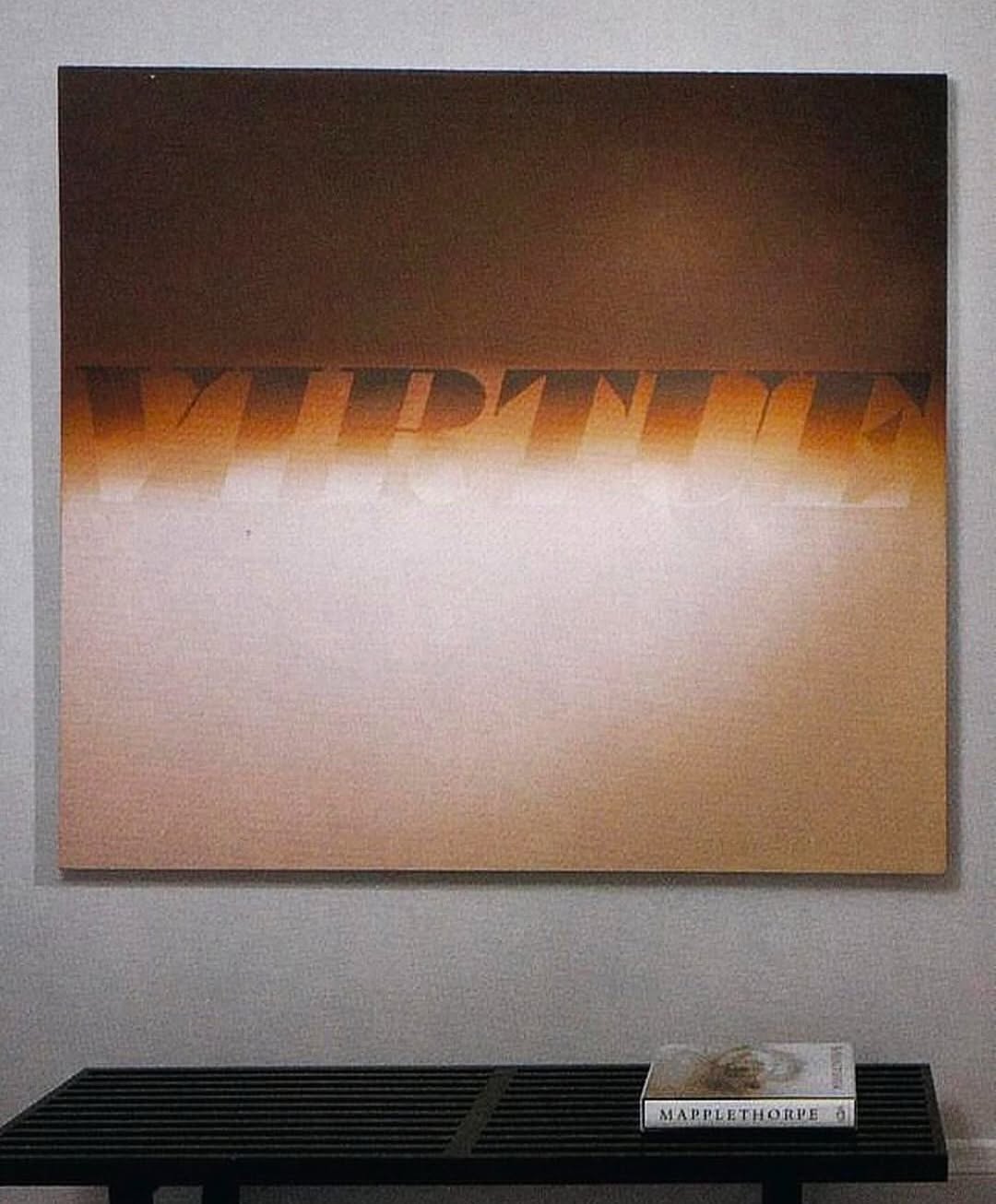

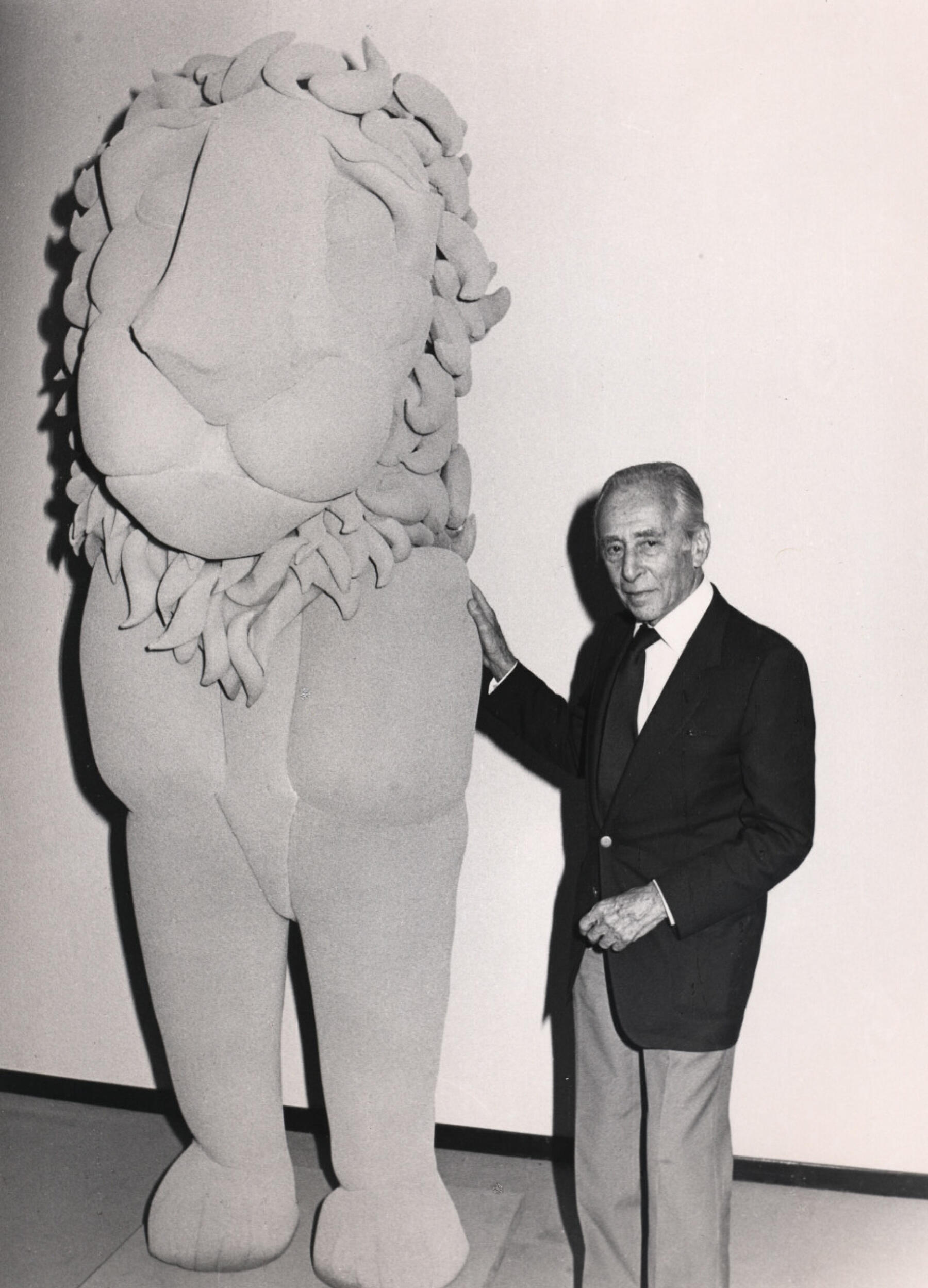

Castelli embraced emerging movements like Pop (Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol), Minimalism (Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Frank Stella), and Conceptual (Lawrence Weiner, Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth). The Whitney Museum’s former director, David A. Ross. once said that, "Wherever the important work was in postwar American art, Leo has been at the center of it.” [10] Castelli’s eye for discovering new talent was affirmed in 1964 when Rauschenberg became the first American to win the major award of the Venice Biennale, the International Grand Prize for Painting.

“I witnessed the shift of the center of the art world from Paris to New York,” Castelli said. “Before, artists had been dependent on European inspiration. But we had here an extraordinary group of original artists for the first time in America.” [11]

Castelli ran his business on mutual trust and respect and gave his artists a stipend whether their work sold or not. A 1980 New Yorker profile recalls an instance in which Castelli’s gallery director, Ivan Karp, suggests cutting John Chamberlain’s stipend in half because he was slow in making work, and owed $40,000 in debt to the gallery. “How could I?” Castelli said. “He couldn’t get along on that.” [12]

From 1968 to 1971, large-scale new media works were shown at a Harlem industrial space known as the Castelli Warehouse. At the top of the ’70s, the gallery moved downtown, further underlining the art world’s movement to SoHo. (His ex-wife Ileana’s Sonnabend Gallery was in the same building). A second SoHo location opened in 1980 and hosted large-scale works. From 1971 to 1981, Castelli took on no new artists. An exception was Julian Schnabel, a co-representation with Mary Boone, the young dealer who rented the gallery downstairs from Castelli. [13]

In 1988, a year when there were no tax deductions for gifts to museums, Castelli gave Rauschenberg's “Bed” (1955) to the Museum of Modern Art. Then valued at $10 million, Castelli bought the work for $1,200 from Rauschenberg’s first show at his gallery in 1958. “Very few people were buying Rauschenbergs at that time, and for me it was logical to buy a painting that I so admired,” he said. “As a matter of fact, it was important in my decision to give Rauschenberg a show.” [14]

Castelli’s personal collection was modest, and he rarely sold. “Well, there are lots of things that I would like to keep if I could afford it, but it is not possible for somebody in my position to be selfish. I have to let things go, let them travel the world,” he said. “But I keep things for myself, too, yes. Especially drawings. Smaller things, not really too important paintings. Those have to go into the world.” [15]

SOURCES

1. Aronson, Steven M.L. “Architectural Digest Visits: Leo Castelli.” Architectural Digest. October, 1995

2. Russell, John. “Leo Castelli, Influential Art Dealer, Dies at 91. The New York Times. August 23, 1999 https://www.nytimes.com/1999/08/23/arts/leo-castelli-influential-art-dealer-dies-at-91.html

3. Oral history interview with Leo Castelli, 1991 October 24. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/archives/transcript_castelli.pdf

4. Oral history interview with Leo Castelli, 1969 May 14-1973 June 8. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-leo-castelli-12370

5. Ibid.

6. Lewis, Jo Ann. “The Mind Heart Of The Master Art Dealer.” The Washington Post. April 11, 1990

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/04/12/the-mind-heart-of-the-master-art-dealer/815d7961-4735-404e-9313-b7eaead8ed52/

7. Thompson, Don. “The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art.” St. Martin's Publishing Group, 2012

8. Freeman, Nate. Why Leo Castelli Paid his Artists Even When They Weren’t Making Work.” Artsy. “July 31, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-leo-castelli-changed-art-market-forever

9. Russell, John. “Leo Castelli, Influential Art Dealer, Dies at 91. The New York Times. August 23, 1999 https://www.nytimes.com/1999/08/23/arts/leo-castelli-influential-art-dealer-dies-at-91.html

10. Strickland, Carol. “Leo Castelli Meets Film Maker and Fan.” The New York Times. May 12, 1991 https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/12/nyregion/leo-castelli-meets-film-maker-and-fan.html

11. Ibid.

12. Tomkins, Calvin. “A Good Eye and a Good Ear.” The New Yorker. May 19, 1980 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1980/05/26/a-good-eye-and-a-good-ear

13. “Mary Boone: The Art of the Dealer.” New York Magazine. April 6, 1998 https://nymag.com/nymetro/news/people/features/2419/

14. Glueck, Grace. “Castelli Gives Major Work to the Modern.” The New York Times. May 10, 1989

https://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/10/arts/castelli-gives-major-work-to-the-modern.html

15. Oral history interview with Leo Castelli, 1997 May 22. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_216332

Image: Photo via Fundación Juan March