Thoughts: Tobias Czudej

AI in Art Valuation: Where Automation Meets Expertise

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej 13/11/2025

Last week I led a panel discussion on AI and the future of art valuation at the Appraisers Association of America’s annual conference at the New York Athletic Club in New York. The session brought together Nicholas Pilz, MAI, SRA, AI-RRS, Chair of the Appraisal Standards Board, and Olivier Berger, Co-CEO of Wondeur Ai, to examine how artificial intelligence is reshaping professional appraisal practice.

Valuing Art: Methodology Across Market, Museum, and Scholarship

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej 24/10/2025

How does art acquire value across commercial, institutional, and academic spheres? Tobias Czudej’s lecture at the University of Hong Kong examined Andrea Fraser’s framework for understanding the contemporary art field – and what it means for appraisal practice.

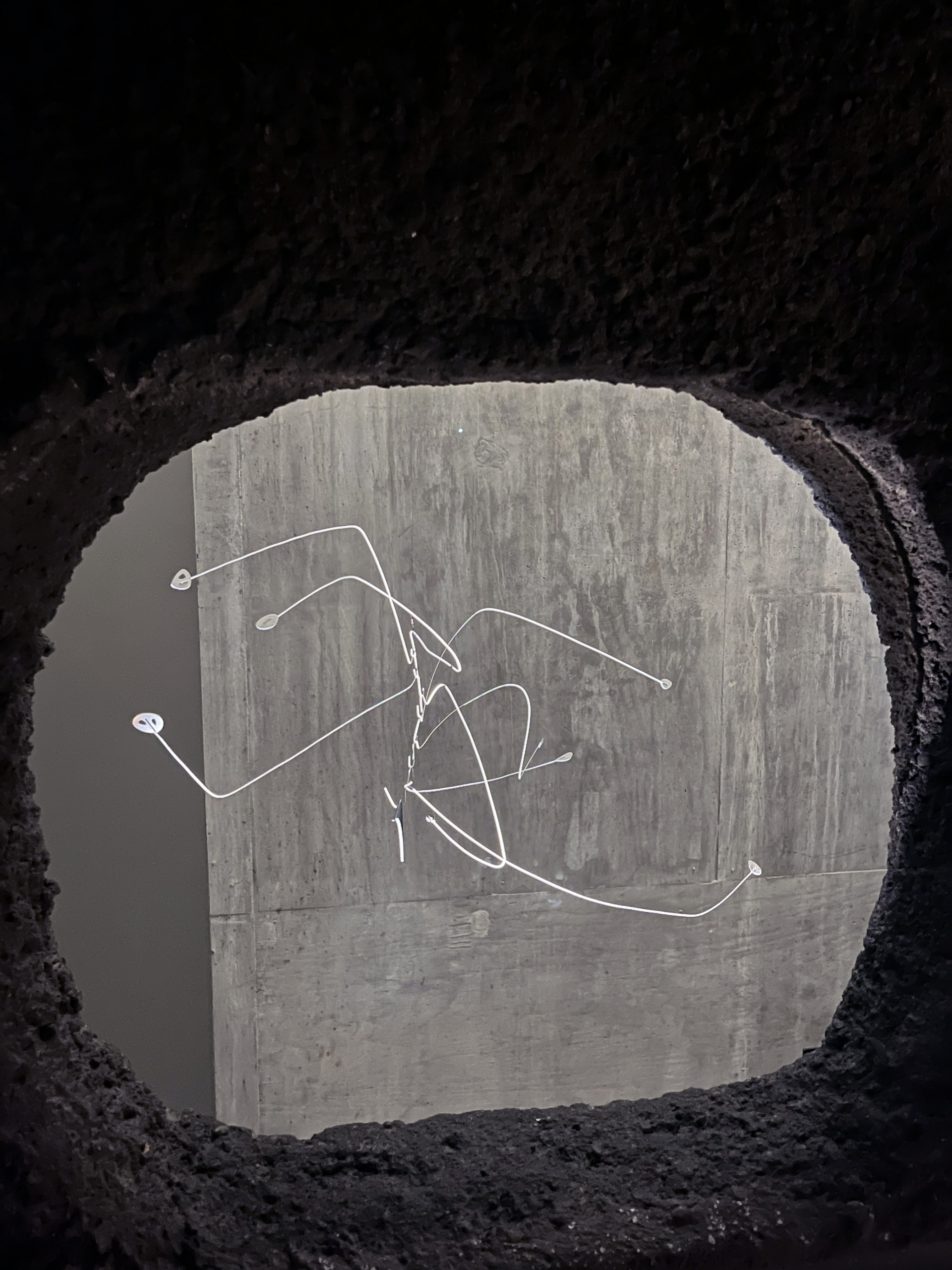

On the Opening of Calder Gardens: The Surprise Element

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej 22/09/2025

On Saturday at the opening of the Calder Gardens in Philadelphia, descending Herzog & de Meuron’s volcanic black stairway, I caught a mobile through what might have been a ship’s porthole—suspended there like a daddy long-legs you might find mangled, still twitching.

The Gochman Family Collection: A Different Approach

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej 18/07/2025

The juxtaposition is deliberate, one suspects. In a traditionally appointed Central Park apartment—the kind of domestic space that has housed American collections for over a century—contemporary Indigenous works by artists such as Ishi Glinsky (Tohono O’odham), Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill (Métis), and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) hang alongside pieces by Alice Neel. The effect is not integration so much as productive tension, raising questions about which narratives have been permitted to coexist within such spaces, and which have been systematically excluded.

Thoughts: John Quinn's 1913 Tariff Battle - Transforming the American Art Landscape

Thoughts: Tobias Czudej 08/04/2025

When we examine pivotal moments that shaped the development of modern art in America, John Quinn’s successful battle against art tariffs in 1913 stands as a transformative achievement. This decisive legislative victory—overturning the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act’s 15 percent duty on contemporary art imports—restructured the American art landscape and established the groundwork for New York’s eventual emergence as a global art center.